Guest post by Suzanne Singletary, Professor and Associate Dean, Thomas Jefferson University

On view at Philadelphia’s Barnes Foundation until January 9, Suzanne Valadon: Model, Painter, and Rebel is the first major retrospective in North America of the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century French artist.

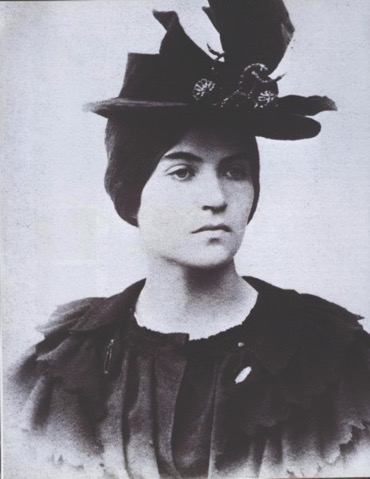

The title insinuates aesthetic daring and psychic transformation within both art and artist, and, in many ways, the show does not disappoint. Starting from Valadon’s early days as a model for some of the most recognizable names in the art history canon, the exhibit tracks her artistic awakening in a sequence of roughly chronological, thematic rooms. The issue of gender is the obvious subtext throughout. (Figure 1)

Valadon as Model: “Maria”

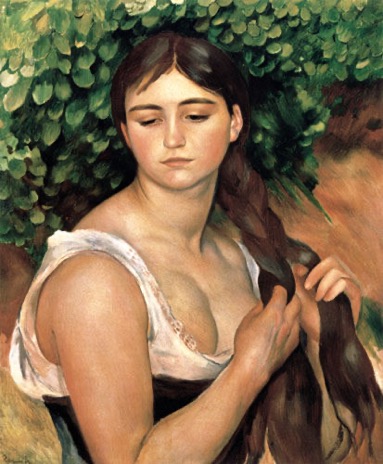

The first room presents Suzanne Valadon (1865–1938) as model and muse whose malleable face and figure—a byproduct of a brief stint as a circus performer—morph variously into a “Renoir” or a “Lautrec” or a “Puvis de Chavannes.” (Figures 2 and 3) The intimation is that the “real” Valadon lay dormant behind her modeling moniker, “Maria.”

Subsequent rooms chronicle her transition to a commercially successful painter who overcame childhood poverty and lack of formal training to be championed by artists of the stature of Auguste Renoir and Edgar Degas; and to exhibit in notable professional venues, including the prestigious Salon of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in Paris,1894.

Though often touted during her lifetime as a “masculine” artist—the ultimate compliment for a “woman painter”—the exhibit foregrounds Valadon’s uniquely feminine interpretation of such classic subjects as the female nude.

Valadon as Artist: “Suzanne”

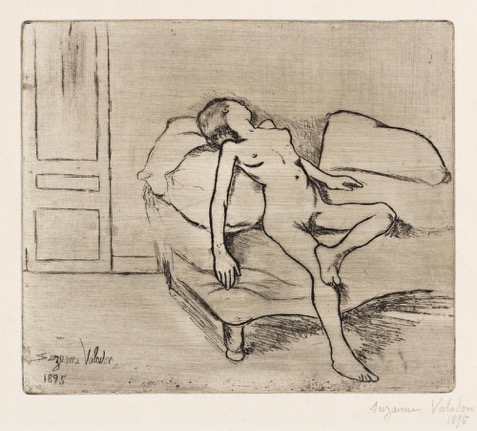

Modeling proved a fertile training ground for Valadon, who absorbed the techniques and processes of her artist-employers. Adopting the forename “Suzanne,” Valadon’s first foray into making art around 1883 was graphic. The drawings and prints in the exhibition broadcast her signature bold contour lines that flatten the nude bodies of women and children, washing and dressing, and appear at-odds with the touches of interior shading. (Figure 4)

The subject of bathers, coupled with their ungainly poses and often awkward combination of head-on and bird’s-eye viewpoints, recalls the work of Edgar Degas, who befriended Valadon in the early 1890s. He became an avid patron and mentor, and introduced her to printmaking. (Figures 5 and 6)

In her most striking images, Valadon’s hard-edge contours serve double duty, at once descriptive and abstract. While illustrative of the objects depicted, her unmodulated, thick outlines also assume a visual life of their own as curvilinear decoration.

Valadon: Portraits

In 1896 Valadon married businessman Paul Mousis, enabling her to retire from modeling and devote herself to painting full time. The Barnes exhibition includes a sampling of her psychologically astute portraits of members of her intimate family circle that shed some light upon the dynamics and challenges of her personal life.

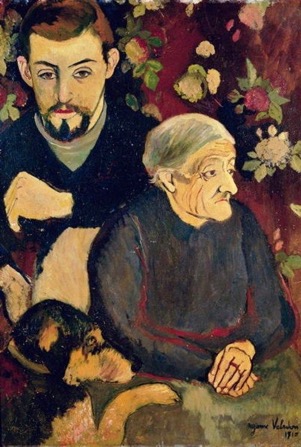

One super-charged image, entitled Family Portrait (1912), depicts Valadon, standing behind her illegitimate son—the troubled painter Maurice Utrillo—who is seated in a dejected pose. To the right is her bent, elderly mother, Madeleine, and behind her stands her son’s friend, twenty-three-year-old painter André Utter, whom she married in 1914 after divorcing Mousis. All the protagonists gaze vacantly into the distance, except Valadon. Painted at age forty-seven, the artist positions herself as fulcrum and anchor, visually and emotionally—and, as the sole breadwinner, financially—of this family unit. The only member to confront the viewer through direct eye-contact, Valadon dominates these cropped, overlapping figures who appear trapped within the compressed space of an airless room. (Figure 7)

The painting entitled Grandmother and Grandson (1910) portrays her son and mother in a similarly cramped, claustrophobic interior whose encroaching, flowered wallpaper recalls the decorative backgrounds of Paul Gauguin. Valadon’s mother served as primary caretaker for the young Maurice, who battled mental illness and addiction. Though fused together, the tension between the two sitters is palpable. (Figure 8)

Smothering familial relationships are again the subplot of Valadon’s portrait Marie Coca and Her Daughter Gilberte (1913), depicting her maternal niece and grandniece. Here the figures of mother and daughter overlap, their dark costumes appearing to fuse; but no warmth is exchanged. Instead mother stares detachedly into space, while her daughter looks out plaintively at the viewer. (Figure 9) Valadon imbues these portraits with acute sensitivity and psychological penetration.

Valadon: The Nude

The theme of the nude dominates the exhibition, taking up two large rooms. During the 1910s and 1920s, Valadon’s career skyrocketed and her reputation was international. Her paintings of nudes, in particular, were artistic and commercial successes, even though the subject was deemed unorthodox, even inappropriate, for a “woman painter.” At the time, women were, in fact, barred from life drawing classes.

Much has been made of Valadon’s former modeling experience that may have evoked empathy towards her models and may explain why she favored unidealized, “real” bodies that fly in the face of convention. Yet, Valadon’s disregard for classical proportions was in synchrony with the approach of many avant-garde painters, such as Gauguin, who similarly rejected academic canons. What is radical about Valadon’s nudes is their lack of coyness or seduction. Instead, their bodies are awkwardly posed, with glaring anatomical distortions, and obvious pubic hair, attributes that clearly undermine the depilated, stereotypical image of “Woman.”

In Gilberte Nude Combing Her Hair (1920), for example, the body is heavily proportioned, flesh modeled in garish, unmodulated tones of light and shade that clash with the flattening effect of the insistent black contour. As in the portraits, the room that surrounds the figure is telling, and in this image is animated with colored patterns and organic lines that recall Art Nouveau interiors. (The visible curvilinear arm of the chair to the right suggests that it might be a popular, mass-produced Thonet chair.) (Figure 10)

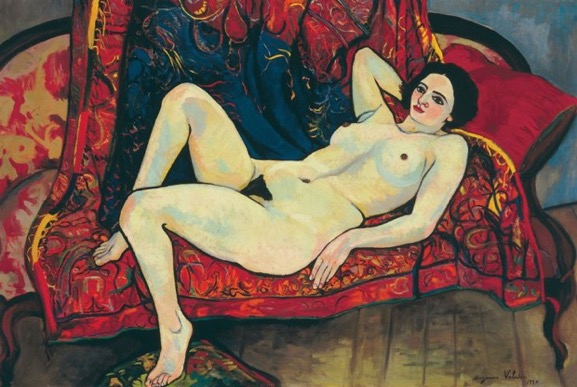

Nude on a Red Sofa (1920) similarly immerses the figure in a riot of colors, patterns, and lines that suggest interiors painted by Henri Matisse. Sporting with the tradition of the reclining Odalisque, the nude’s body seems elastic, with elongated limbs and torso, topped by a miniscule head; her eyes directly engaging the viewer. (figure 11) Such anatomical liberties harken back to the figural distortions in Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s Grand Odalisque (1814) with her conspicuously additional vertebrae. In short, Valadon reapportioned the female body to “make a painting,” while simultaneously assigning to her models a sense of personal agency.

Valadon: Rebel

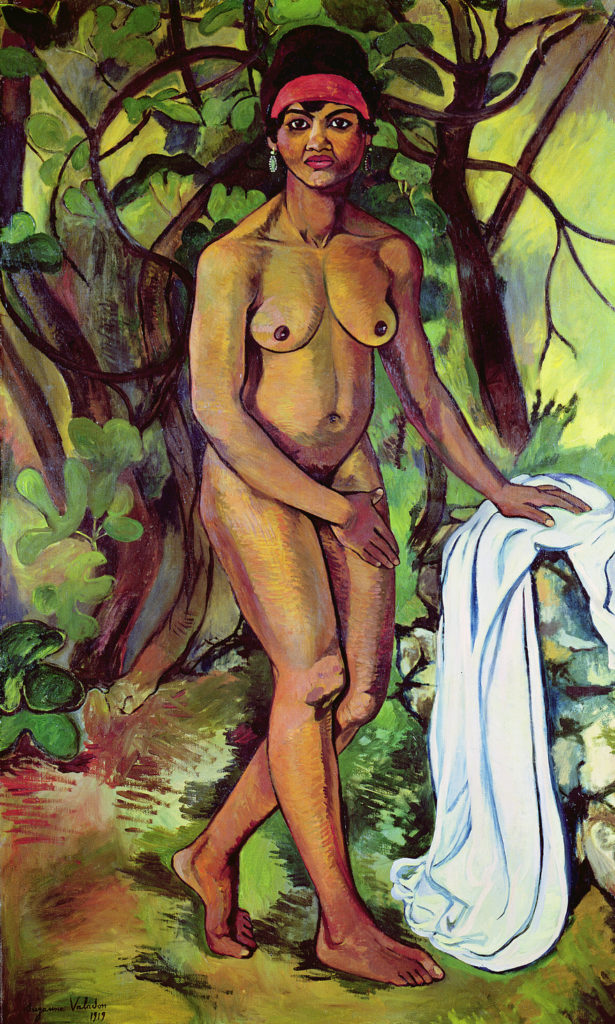

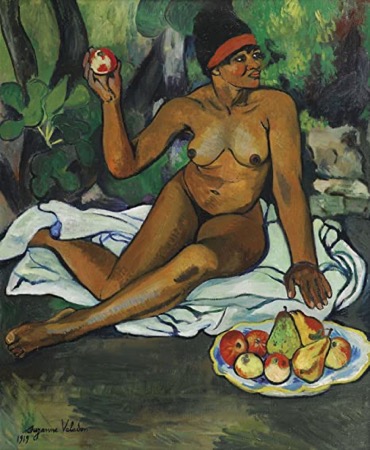

Intriguing is Valadon’s series of five nudes, dated 1919 and featuring the same black model. Only two of the paintings have been located, and both are on display at the Barnes. Titled Black Venus (Figure 12) and Seated Woman Holding an Apple (Figure 13), both images cast the black female body—a highly contested subject, associated at the time with slavery, colonialism, and hyper-sexuality—in the role of Greek goddess and biblical Eve, respectively.

Once again, Valadon both engages and thwarts convention, upending viewer expectation. (Extant photographs of the remaining three paintings have been identified as “reclining slaves,” though it is not known if this was Valadon’s title.) Valadon’s depiction of the full-frontal male nude marks another of the artist’s radical moves. In Adam and Eve (1909), Valadon casts herself as the naked Eve, accompanied by Utter as the naked Adam. (Figure 14)

Now covered by a modest wreath of painted vine leaves, an effort to thwart censorship when exhibited in 1920, the frank depiction of male genitals is considered a first by a woman painter, equaled by an additional first, her own full-length, frontal nude self-portrait.

Valadon: Late Works

The final room of the exhibition provides a small sample of Valadon’s boldly colored and patterned still-life paintings as well as insightful portraits from the 1920s and 1930s. These works testify to the devotion to figuration that characterized her nearly 50-year career.

Of the late paintings on display, perhaps the most affective image is a stark Self-Portrait (1927). Turning the mirror onto her 66-year-old self, the artist stares steadily at her own reflection. Her lined, haggard face confronts the physical ravages of time, while her unwavering gaze asserts strength and resilience. (Figure 15)

Valadon: Today

Among the advantages of any retrospective is the opportunity to experience the trajectory of an artist’s development; to put isolated images into broader historical and artistic contexts; and to ascertain innovation in dialogue with the work of peers. Suzanne Valadon: Model, Painter, Rebel is a long-overdue corrective to the dearth of such critical commentary afforded Valadon, whose bohemian lifestyle and dubious distinction as an “artist’s model”—implying a woman of easy virtue—overshadowed her art. For Valadon, the personal and the artistic intertwined with the commercial. All three demands she skillfully negotiated. While attentive to the art of her times, Valadon took artistic risks to forge a distinctive style and to actualize a personal vision. In her words, the “construction of my canvases, [were] designed by me, but driven always by the emotion of life.”

Suzanne Singletary, Ph.D. is Professor of Art and Architectural History and Associate Dean in the College of Architecture at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. She has published on Eugène Delacroix, French Symbolism, and Francesco Goya, and contributed essays to Impressionist Interiors (National Gallery of Ireland, 2008), Therese Dolan’s Perspectives on Manet (Ashgate, 2012) and James Rubin’s Rival Sisters (Ashgate, 2014). Her book James McNeill Whistler and France: A Dialogue in Paint, Poetry, and Music was published by Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group (2017).

Suzanne Valadon: Model, Painter, and Rebel is on at The Barnes in Philadelphia through January 9, 2022. Following this world premiere, the exhibition travels to Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen, in 2022, where it will be the first exhibition of its kind in Scandinavia.

More Art Herstory posts about French women artists:

Louise Moillon: A pioneering painter of still life, by Lesley Stevenson

Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris, A Review, by Alice M. Rudy Price

Marie Laurencin and the Autonomy of Self-Representation, by Mary Creed

Rosa Bonheur—Practice Makes Perfect, by Ien G.M. van der Pol

Victorine Meurent, More than a Model, by novelist Drēma Drudge

Marie-Thérèse Reboul Vien: Finding the Natural in the Neoclassical, by Tori Champion

Madeleine Françoise Basseporte’s Hyacinths at the French Court, by Mary Creed

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard: Artist, Friend, Teacher, by Jessica L. Fripp

Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Revolutionary Painter, by Paris Spies-Gans

Seductive Surfaces: Anne Vallayer-Coster’s Vase of Flowers and Conch Shell at the Met, by Kelsey Brosnan

The Theatrical Wonders of Jeanne Paquin’s Belle Époque Parisienne, by Julia Westerman

Paper Portraits: The Self-Fashioning of Esther Inglis, by Georgianna Ziegler

More Art Herstory exhibition reviews:

Blanche Hoschedé-Monet: An Artist in Her Own Right, by Rebekah Hoke Brown

Women Artists at the Cape Ann Museum, by Erika Gaffney

Early Modern European Women Artists at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, by Erika Gaffney

Carlotta Gargalli 1788–1840: “The Elisabetta Sirani of the Day,” by Alessandra Masu

Masters and Sisters in Arts, by Jitske Jasperse

Thérèse Schwartze (1851–1918), by Ien G.M. van der Pol

Thoughts on By Her Hand, the Hartford Iteration, by Erika Gaffney

Plautilla Bricci: A Painter & “Architettrice” in Seventeenth-century Rome, by Alessandra Masu

In defense of monographic exhibitions of female artists: The case of Fede Galizia, by Camille Nouhant

The Ladies of Art are in Milan, by Cecilia Gamberini

“Artemisia” at the National Gallery: A Review, by Sheila McTighe

Artemisia Gentileschi: What Wasn’t in the London Exhibition and Why it Matters, by Jesse Locker

“La grandezza del universo” nell’arte di Giovanna Garzoni / “The grandeur of the universe” in the art of Giovanna Garzoni, by Sara Matthews-Grieco

By Her Hand: Personal Thoughts and Reflections on an Exhibition, by Oliver Tostmann

Thoughts on Feminist Art History in the Wake of Artemisia: Vrouw & Macht at Rijksmuseum Twenthe, by Jitske Jasperse

A Tale of Two Women Painters, Guest post / exhibition review by Natasha Moura

Other Art Herstory guest posts you might enjoy:

Unpacking the Exhibition: Blanche Hoschedé-Monet in the Light, by Haley S. Pierce

Helen Allingham’s Country Cottages: Subverting the Stereotype, by Amy Lim

Happy Birthday, Fidelia Bridges! by Katherine Manthorne

Esther Pressoir: Imagining the Modern Woman, by Suzanne Scanlan

Anna Boberg: Artist, Wife, Polar Explorer, by Isabelle Gapp

The Abstract-Impressionism of Berthe Morisot and Joan Mitchell, by Paula Butterfield

The Theatrical Wonders of Jeanne Paquin’s Belle Époque Parisienne, by Julia Westerman

From a Project on Women Artists: The Calendar and the Cat Lady, by Lisa Kirch

The Life and Art of Dorothea Tanning, by Victoria Carruthers