A celebrated portraitist returns to Delft

Guest post by Ien G.M. van der Pol, www.ienvanderpol.nl

This exhibition of the work of a celebrated nineteenth-century Dutch woman artist is held in the Paul Tetar van Elven Museum, delightfully situated on one of the narrow canals in Delft. Paul Tetar van Elven (1823–1896) was an academic painter who lived in this house for thirty years. And when he died, he left everything as it was in order to be a museum for his paintings and his Delft Blue collections. So entering the premises, you still have the feeling you could bump into him at any moment. His living rooms, his studio, nothing has changed in this big house which is now a small museum. Even the toilet is worth a visit.

It is unclear if van Elven knew Thérèse Schwartze and whether they ever met. He might have seen her work, as her very first exposition ever was at the 1871 Exhibition of Female Craft & Art in the Town Hall in Delft. She was twenty years old then. And now, 130 years later, she’s back in Delft. With fifty of her art works.

Three queens

Entering this intimate house-museum, we come into the hall. My attention was drawn towards two large family portraits on the left, both quite similar and yet so different. But first one has to pass the queens.

In her days, late nineteenth- to early twentieth-century, Thérèse Schwartze was a well known and celebrated portraitist of the aristocracy, including Dutch royalty. In 1880 Thérèse was invited to stay at the Royal Palace (“Paleis Soestdijk” in Baarn) for a while, in order to give painting lessons to princess Marie, a niece of regent-queen Emma 1858–1934). Soon to follow was a commission for a portrait of Queen Emma with the little princess Wilhelmina, who was born in 1880. This portrait now on view in the Paul Tetar Museum—without baby Wilhelmina—is from the same period. The young queen is set in dark colors and a neutral background, apart from her face. In this painting, one can already see the fine art of portraiture and painting material that Thérèse fully mastered. The fur stole, the lace cap on her head, as well as the brocade of the queen’s robe.

Thérèse’s liaison with the royal family of the Netherlands lasted through a period of thirty-five years and gave her six commissions that contributed greatly towards her fame and wealth. Most royal portraits were of Queen Wilhelmina, of which the stately inauguration (1898) portrait in oil is the most well known. In this exposition we encounter a later work in pastel colors.

There is a second version of this portrait which she made in 1911, also in pastel. This one remained in Thérèse’s possession and was displayed at various exhibitions. In 1916 she donated it to the Amsterdam artist society “Arti et Amicitiae,” of which she was a member all her working life.

The third queen (to be) present in the hall is Crown Princess Juliana (1909–2004) at one year of age. Next to it is a photograph of the baby in a similar position, very likely used as an aid for this portrait. I noticed that in the photograph she looks like a baby, whereas in the oil painting she already looks like a little queen.

“Her client was king”

Thérèse Schwartze was not only commissioned by aristocracy and royalty; she also painted the “nouveau riche,” such as industrialists, merchants and bankers. And she was able to ask truly high prices (in guilders those days), helping her to provide for her family after her father’s death in 1874.

Turning towards the other side of the main hall, we see two large family portraits—seemingly similar, but what a striking difference!

When I first set eyes on the first of these two pictures, my immediate thought was: what’s the matter with the mother? (Must be my former profession as a trauma counsellor.) We see a fairly young woman, seemingly lost into her own thoughts, while her children either cling to her or to one another. Later on, learning more about the background of this lady, it was clear that she had quite a hard life. Her husband was a successful stockbroker, a politician in the provincial states of North and South Holland as well as a board member of the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam. There was no lack of money but he also loved to spend it. When he died in 1914, he left his family penniless. Aleida must have suffered greatly; she was admitted to a psychiatric institution, where she died in 1944. Is that what I saw?

Apparently the Ogtrop family gave Thérèse no special instructions as to how they wanted her to portray them. So Thérèse did what she did best: she paid close attention to painting their faces as she met them. And she “went wild” almost in a 19th-century impressionist style on the fabrics, in loose brush strokes and clear light. And all this in an informal setting, giving this enormous portrait a rather “modern” appearance.

Next to this large Ogtrop family portrait we see a second one, equally brilliant but much more formal in style. According to art historian Cora Hollema, this difference in style was not due to a development of the painter, but to the wishes of her client. Mr. & Mrs. Boissevain, well-to-do members of the Amsterdam upper class, had ten children, six daughters and four sons. They knew Thérèse’s portrait of Aleida and her children, but found it “far too modern.” So in 1916 they asked Thérèse to make a more traditional portrait of their daughters. No problem for Thérèse, she knew her “classics.” As she was the bread winner, she pragmatically adapted her style according to her client’s demands—hence the title of this exhibition: “Her client was king.”

Whatever the style Thérèse adapted to, all her portraits reflect her skill in capturing the character of her sitters. Her portrayal of expressions reveals how people show more of their personality than they realise. There is always a certain liveliness in her likenesses, with striking resemblance of faces, warm colors and masterful brush strokes where clothing is concerned. And many of them can now be seen at this house-museum.

Family and friends

Apart from her commissions, Thérèse also made portraits of family and friends, for pleasure and of course without a price. She often gave them away to the subject as a present for their birthday or for Christmas. She did show some of them at exhibitions, but they were never for sale. Her free work is indeed more “free,” loosely painted and faster, as we can see in a few examples below.

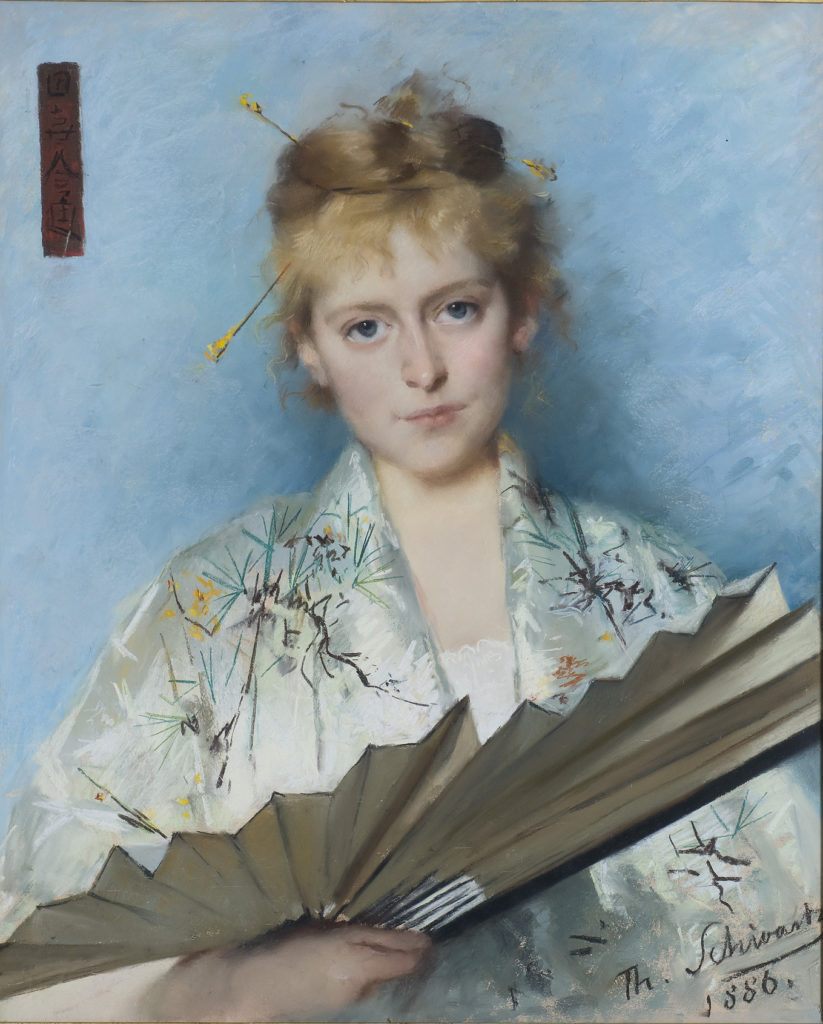

In 1884, Thérèse went to Paris, as many painters did, together with her good friend and colleague Wally Moes (1856–1918). They stayed for over four months and were very productive, submitting works to the Salon in the spring of that year. It was in Paris that Thérèse made this portrait of her friend.

Thérèse Schwartze mostly worked in oil, but she was equally skilled in pastels and charcoal. Charcoal was her favourite and she made several self-portraits in this material. She regretted that her paying clientele “did not like charcoal.” However, she made a few wonderful portraits of another friend of hers, Mia Cuypers (daughter of architect Pierre Cuypers of the Rijksmuseum and the Central Station in Amsterdam) in pastel, as well as in charcoal. Both are on display in the Paul Tetar Museum.

This portrait clearly shows Thérèse’s virtuosity with pastels. The fan seems to come out from the painting; the silk kimono is almost tangible. The blond Mia dressed in this Eastern style was very controversial at the time, as was her marriage to a Chinese man.

In the “Purple Room” of the museum we can see another portrait of Mia, this time made in charcoal.

On the back of this picture we see an interesting drawing: a charcoal study for the painting Italian woman with dog Puck.

Italian models

Climbing the wooden stairs of the museum, we arrive at the first floor where not only Wally Moes’ smile greets us, but also many colorful portraits of more exotic subjects.

When Thérèse Schwartze and her fellow-painter Wally Moes were in Paris, they very often hired “the Italian models.” These were poor peasants, gypsies and shepherds who came from Ciociara (southeast of Rome) in order to earn some money by sitting for the numerous painters that had gathered in Paris. Thérèse painted them mostly in their traditional Ciociara costumes—bright colors and lively faces.

Compare this with the “glance” of the other Italian girl, present in this exhibition.

Most of her Italian portraits now on display in the Paul Tetar Museum, however, are of adults—mostly women—in their Ciociara costumes.

As we leave the upper room, we are sent off by the big smile of Charles Wesley Payne (1849?–1921). He was a singer in the Fisk Jubilee Choir that travelled the world to raise funds for the first Afro-American university, Fisk University in Nashville. It was founded after slavery was abolished in 1865. The choir of four men also performed in Amsterdam in 1900. Thérèse was quick to invite them over for a house concert at her home and to sit for her, which Wesley did. She dressed him up in Eastern style and quickly painted him in bright colors with fast strokes. Just look at the “impression” of a ring on his hand in the detail picture.

All this beauty and so much more, like self-portraits, loving portraits of her husband, sisters, parents and many others, can be seen at the Paul Tetar Museum in Delft. Each of the fifty paintings has a story, many of which can be read and seen in the showcases, which contain letters, newspaper clippings and photographs.

The exhibition is curated with great care and attention by guest curator Cora Hollema, who does a lot of research on Thérèse Schwartze, and Alexandra Oostdijk, director of the museum. Hollema is the author of the book Thérèse Schwartze: Painting for a Living.

Because of the winter-lockdown in The Netherlands, the exposition has been prolonged and can be enjoyed until May 8, 2022.

If you happen to be in The Netherlands, Thérèse Schwartze is certainly worth your visit.

Concise biography of Thérèse Schwartze

Thérèse Schwartze was born on December 20, 1851, in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. She was the daughter of the painter Johan Georg Schwartze, from the Northern Netherlands, who grew up in Philadelphia and trained in Düsseldorf.

She received her first training from her father, who was very strict and taught her well. She then studied for a year at the Rijksacademie van Beeldende Kunsten (State Academy of Visual Arts). She then travelled to Munich and studied under Gabriel Max and Franz von Lenbach. In 1879 she went to Paris to continue her studies under Jean-Jacques Henner; she later returned to Paris with her painter-friend Wally Moes. When she returned to Amsterdam she became a member of Arti et Amicitiae, an art society of which she was a member all her life.

Ien G.M. van der Pol is a retired trauma specialist, now an art collector of nineteenth-century female painters of the Lowlands (Netherlands & Belgium). Follow her on Twitter and/or connect with her on LinkedIn!

Thérèse Schwartze: “Her Client was King” is on at Paul Tetar van Elven Museum in Delft through May 8, 2022.

More Art Herstory posts about Dutch women artists

Women and the Art of Flower Painting, by Ariane van Suchtelen

From a Project on Women Artists: The Calendar and the Cat Lady, by Lisa Kirch

Anna Maria van Schurman: Brains, Arts and Feminist avant la lettre, by Maryse Dekker

Books, Blooms, Backer: The Life and Work of Catharina Backer, by Nina Reid

Alida Withoos: Creator of beauty and of visual knowledge, by Catherine Powell

Gesina ter Borch: Artist, not Amateur, by Nicole E. Cook

A Clara Peeters for the Mauritshuis, by Quentin Buvelot

Floral Still Life, 1726—A Masterpiece by Rachel Ruysch, by Lawrence W. Nichols

Women Artists of the Dutch Golden Age at the National Museum of Women in the Arts

The Rijksmuseum Opens Its “Gallery of Honor” to Women Artists

The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian, by Emma Steinkraus

Susanna Horenbout, Courtier and Artist, by Kathleen E. Kennedy

Curiosity and the Caterpillar: Maria Sibylla Merian’s Artistic Entomology, by Kay Etheridge

More Art Herstory posts about 19th-century women artists

Carlotta Gargalli 1788–1840: “The Elisabetta Sirani of the Day,” by Alessandra Masu

Rosa Bonheur—Practice Makes Perfect, by Ien G.M. van der Pol

The Rich and Complex Character of May Morris, Designer, Embroiderer, Jeweller and Writer, by Thomas Cooper

Marie Spartali Stillman’s The Last Sight of Fiammetta, by Margaretta S. Frederick

Visual Feasts: The Art of Sarah Mapps Douglass, by Erika Viola

Evelyn De Morgan: Painting Truth and Beauty, by Sarah Hardy

Portraying May Alcott Nieriker, by Julia Dabbs

The Ongoing Revival of Matilda Browne, American Impressionist, by Alexandra Kiely

The Theatrical Wonders of Jeanne Paquin’s Belle Époque Parisienne, by Julia Westerman

What an excellent review!

We thoroughly enjoyed reading this personal and highly descriptive narrative giving us much insight into the life and work of this very talented artist; Thérèse Schwartze.

Thank you very much.