Guest post by Nina Reid, MA student of Art History, University of Amsterdam

Today marks the 255-year anniversary of the death of flower painter Catharina Backer (Amsterdam 1689–Leiden 1766). She grew up surrounded by her father’s great art collection and was spoon-fed a love for art from childhood onward. She developed into an accomplished amateur painter.

A cultured upbringing

As the Backer family was one of the most prosperous families in Amsterdam, Catharina Backer grew up in a wealthy environment. Her family moved in intellectual circles in which a lot of value was attached to a good education. While other affluent people only taught their daughters skills such as dancing, courtesy, or the right table manners for girls, Catharina’s parents offered her a broader education. She learned about literature and the arts, and developed into a well-educated and well-read woman. She spoke English, Italian, and French; and she read about history, art, music, and religion. This was unusual; generally only the children of the nobility received so comprehensive an education.

The Amsterdam canal house where her family lived was full of paintings and drawings, and Catharina admired her family’s impressive art collection from an early age. In many prosperous families, children received drawing and painting lessons, as did Catharina and her brother Cornelis. Her family loved her enthusiasm, as the Backer family correspondence documents. Catharina’s parents hoped that the lessons would offer their daughter some distraction from her melancholic tendencies. In Catharina’s correspondence with her father, Willem Backer often expressed his concerns about her wistful state of mind.

Catharina is the only Backer to have created an artistic oeuvre, although it was probably not her ambition to become a professional artist. More and more well-off men and women in the eighteenth century became dilettantes, who were taught painting primarily to dispel boredom. After a broad artistic education, Backer eventually specialized in still lifes of flowers and fruits (fig. 1). It is unclear who taught Backer to paint, although there has been speculation. Possible masters include Jan and Justus van Huysum and the famous female still life painter Rachel Ruysch.

Backer’s album

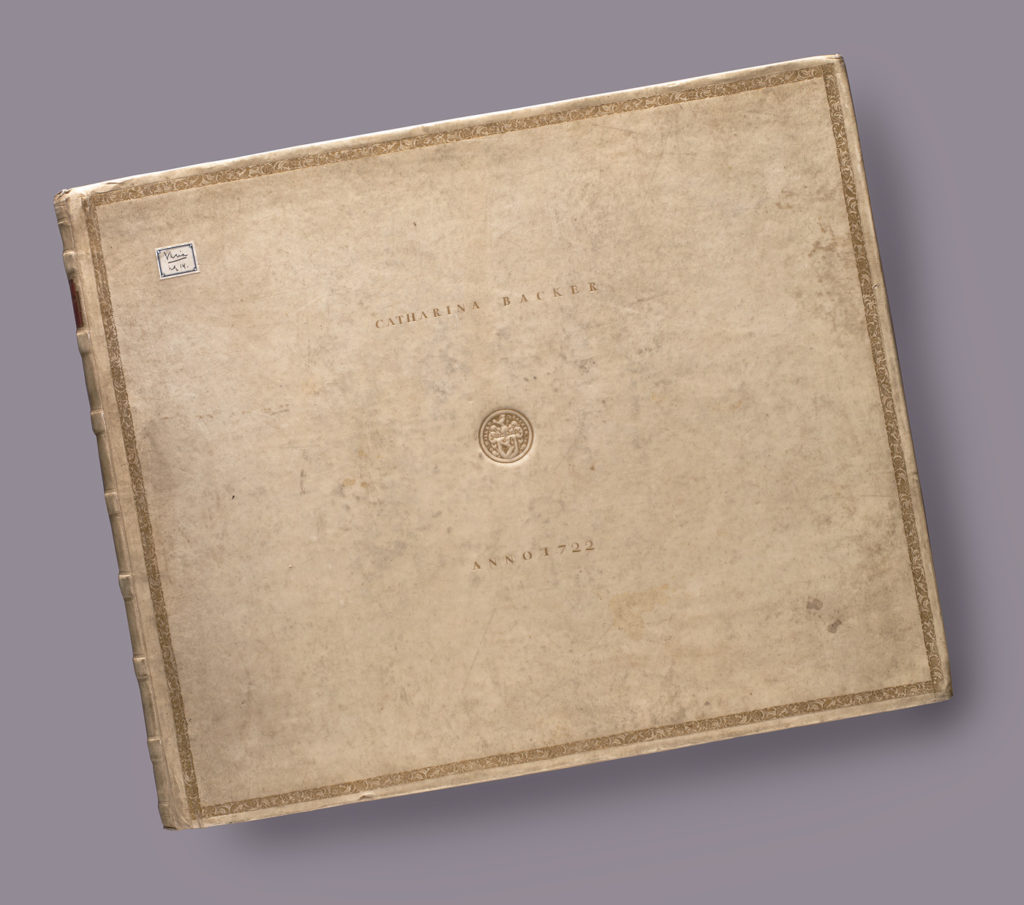

The Amsterdam Museum owns an album with 205 of Catharina Backer’s drawings. (fig. 2) It is probably assembled from the seven albums she brought with her to Leiden after her marriage. Her husband (and first cousin) Allard de la Court included the albums in his catalog of his possessions in 1849. Backer filled the albums with, among other things, studies of body parts and copies of well-known works of art. She also depicted historical figures and scenes of her own invention. Generally, female artists were not associated with such topics. They had no access to the nude models that were often required for painting these kinds of subjects and scenes. Backer occupied herself with “feminine” themes even in her historical scenes, drawing biblical and historical figures such as the Virgin Mary and Cleopatra. She also painted a fan on which a young woman, possibly herself, is led to an allegorical figure of “painting” (fig. 3).

Drawing from life

Backer’s later drawings depict flowers, fruits, and insects (fig. 4 & 5). These are very detailed and executed in oil, watercolor, and gouache. “Naar ‘t leven” (“from life”), she wrote on them: these were not copies of other works of art, but studies after nature. This marks the end of Catharina Backer’s artistic education. She no longer copied others; rather, she created her own images.

Fig. 5 (right). Catharina Backer, Trollius, Tulip (two kinds) and Soapwort, before 1711. Oil and pencil on paper, 205 x 327 mm. Amsterdam, Amsterdam Museum, TB 5932.

Backer preferred to paint flower arrangements (fig. 6). Both critics and the art market considered still life a “low” theme. Backer’s propensity for the subject has caused several art historians to wonder why she did not focus on the more popular history pieces she was clearly capable of creating. However—according to her correspondence with her father—she simply got the most joy from drawing and painting flowers, butterflies, and fruit.

As a dilettante, Catharina Backer was free to choose her own subjects, without having to take the market value of a subject into account. Yet her talent did not go unnoticed: “tender, extensive and very well treated,” contemporaries called her work. Tulips, peonies, and honeysuckle proliferate on her two surviving canvases. Insects and butterflies crawl around and over the bouquets. Backer elevated her “low” subject matter with her artistic skill.

Marital melancholy

After Catharina Backer married, her father repeatedly advised her to keep developing herself both intellectually and artistically. She took not only her art, but also a considerable amount of literature, with her to the Rapenburg, the imposing Leiden building where she lived with De la Court (fig. 7). She kept her art collection in a small room in the back of the house, but she hardly added anything to it. In fact, it seems that she stopped drawing and painting altogether shortly after her marriage.

In 1712, a year after Backer’s wedding, her father complained in a letter to his brother-in-law about how Catharina no longer made art. He feared that his daughter would get bored and start feeling melancholic again. Catharina Backer’s years in Leiden were indeed not very happy. She lost two of her four children at an early age and later, her twenty-three-year-old daughter Sara also died. Her son Pieter was mentally handicapped and required a lot of time and care. On top of that, her beloved father passed away in 1731. His death caused a prolonged family dispute over the inheritance, which isolated Backer from her family; after all, she had to stand on the side of the De la Courts.

However, Backer may have picked up painting again in her later years. An anonymous descendant of Backer wrote in 1857 that as a widow, from 1755 onwards, she “kept herself busy exclusively with the arts.” She presumably would have used her father, husband, and son’s art cabinets as a subject of study. Unfortunately, no work from this period has survived.

Portrait of the painter

Catharina Backer’s wealthy upbringing allowed her to profit from the art collection and the education opportunities available to her. Her great loves were reading, and drawing and painting flower still lifes. When Arnold Boonen painted her portrait in 1713, she clearly displayed this: there she is, surrounded by an easel, a basket of flowers and a pile of books (fig. 8). She showed the world that she was a well-educated, artistic woman. Catharina Backer still fascinates art historians; her story shows how a wealthy dilettante lived, learned, and created an oeuvre which was entirely her own.

Nina Reid is an Amsterdam-based master’s student of art history and research intern at the Dordrechts Museum. She has worked as a research intern at the Amsterdam Museum and as a research intern and assistant at the Van Gogh Museum. She has published about Dutch eighteenth- and nineteenth-century draughtsmanship at the Amsterdam Museum. She has previously written about Catharina Backer in Gouden vrouwen: van kunstenaars tot verzamelaars (red. Judith Noorman, 2020).

Other Art Herstory blog posts about natural history painters:

Louise Moillon: A pioneering painter of still life, by Lesley Stevenson

Rachel Ruysch’s Vase of Flowers with an Ear of Corn, by Lizzie Marx

Women and the Art of Flower Painting, by Ariane van Suchtelen

Marie-Thérèse Reboul Vien: Finding the Natural in the Neoclassical, by Tori Champion

Barbara Regina Dietzsch: Enlightened Flower Painter, by Andaleeb Badiee Banta

Madeleine Françoise Basseporte’s Hyacinths at the French Court, by Mary Creed

Curiosity and the Caterpillar: Maria Sibylla Merian’s Artistic Entomology, by Kay Etheridge

Women in Zoological Art and Illustration, by Ann Sylph, Librarian of the Zoological Society of London

Alida Withoos: Creator of beauty and of visual knowledge, by Catherine Powell

Floral Still Life, 1726—A Masterpiece by Rachel Ruysch, by Dr. Lawrence W. Nichols

The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian, by Prof. Emma Steinkraus

Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750)

Other Art Herstory blog posts about Dutch or Flemish women artists:

The Possibility of Michaelina Wautier, by Allison van den Hoek

Historic Women Artists and Still Life at The Hyde Collection, by Erika Gaffney

Rachel Ruysch: The Art of Nature, by Stephanie Dickey

Rachel Ruysch at Munich’s Alte Pinakothek, by Erika Gaffney

Thérèse Schwartze (1851–1918), by Ien G.M. van der Pol

Anna Maria van Schurman: Brains, Arts and Feminist avant la lettre, by Maryse Dekker

From a Project on Women Artists: The Calendar and the Cat Lady, by Dr. Lisa Kirch

Levina Teerlinc, Illuminator at the Tudor Court, by Louisa Woodville

Gesina ter Borch: Artist, not Amateur, by Dr. Nicole E. Cook

A Clara Peeters for the Mauritshuis, by Dr. Quentin Buvelot

Women Artists of the Dutch Golden Age at the National Museum of Women in the Arts

Susanna Horenbout, Courtier and Artist, by Dr. Kathleen E. Kennedy

Other Art Herstory blog posts about 18th-century women artists:

Anna Dorothea Therbusch: A Woman Painting Against Eighteenth-century Odds, by Stephanie Pearson

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard: Artist, Friend, Teacher, by Jessica L. Fripp

Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Revolutionary Painter, by Paris Spies-Gans

Seductive Surfaces: Anne Vallayer-Coster’s Vase of Flowers and Conch Shell at the Met, by Kelsey Brosnan

Trackbacks/Pingbacks