Guest post by Consuelo Lollobrigida, University of Arkansas Rome Center

Inside the Church of San Luigi dei Francesi, in Rome, there is a beautiful baroque chapel created by Plautilla Bricci, the only woman architect of early modernity.

Plautilla’s youth and artistic training

Celebrated for arte della pittura e architettura (the arts of painting and architecture), as reported by the biographer Filippo Baldinucci, Plautilla was born in Rome on August 13, 1616, to Giovanni, a versatile and eclectic intellectual and artist, and Chiara Recupita, a Neapolitan woman who was related to Ippolita, one of the most illustrious opera singers of her times.

Plautilla received her early artistic education from her father, who facilitated her attendance in the academy of Cavalier d’Arpino, Giovanni’s friend and the godfather of Virginia, Plautilla’s elder sister.

Plautilla’s earliest known work is a Madonna and Child (fig. 1) in the Carmelite church of St. Maria in Monte Santo. Painted at the beginning of the 1630s, according to Pietro Bombelli, the execution of the canvas was associated with a miraculous event. It seems that Plautilla initially highlighted the body of the Baby Jesus and then that of Mary. At the moment she was ready to put her brushes and colors on the face of the Virgin, she fell asleep. When she woke up, the face was completed, as though by a divine hand. To acknowledge the episode, the family decided to donate the painting to the adjacent church of Santa Maria, which was then under construction; and in 1659, the sacred image received the golden crown from the Chapter of St. Peter (an honor accorded to images of the Virgin with which any kind of miracle was associated).

Network and patrons

Some sources tie Plautilla’s training to Eufrasia Benedetti della Croce, a Carmelite nun and accomplished painter living in a convent in Capo le Case. Eufrasia’s brother Elpidio Benedetti was the agent in Rome of Cardinal Mazzarino (Cardinal Mazarin), and a key figure in the Roman art world, who eventually became Plautilla’s most important patron.

Still other records tie her to the Barberinis’ circle. There is a November 15, 1644 entry in the account books of Cardinal Francesco Barberini of a payment of 30 scudi paid to Bricci for two works, a Saint Francis and an Angel and a Floral still-life. A few months later, the humanist Giacomo Albano Ghibbesio mentions her in his inventory: “due grandi in argento, e oro, dipinte con le mie armi dalla Plautilla” (“two doors in leather, silver and gold with my coat-of-arms painted by Plautilla”).

Regrettably, the famous cabinet Bricci painted for Antonio degli Effetti is now lost. Its beauty was described in his Studiolo di pittura nella Galleria della Ricchezza, and in Giovan Pietro Bellori’s Nota delli Musei.

In 1655. the artist is documented as pittrice at the Accademia di San Luca, where she is still mentioned in 1671. So we know that she participated uninterruptedly in the life of the Academy, which was the first institution of its kind to enroll women (beginning in 1607).

Meanwhile, Plautilla cultivated important relationships with the most inspiring cultural and artistic protagonists of the time. Both her father’s alliances and connections and her friendship with Elpidio Benedetti smoothed the way for Plautilla to join the gran Theatro del mondo and successfully challenge the undeniable prejudices against women in Roman society.

Italy’s first woman architect

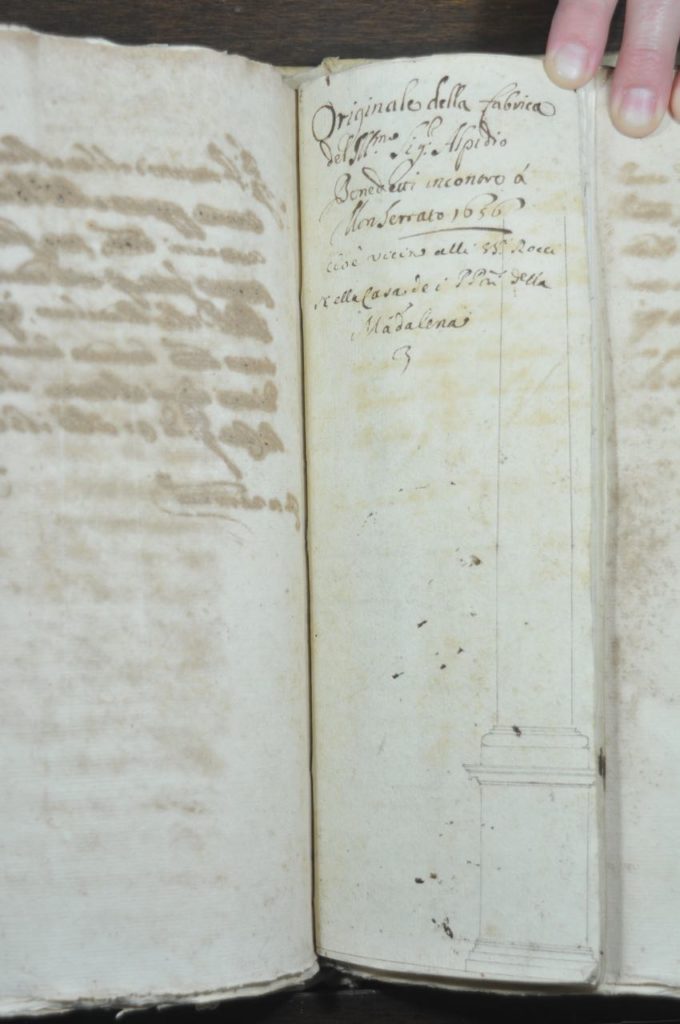

However, it is still a mystery how she managed to become an architect, since the profession was decidedly reserved for men. A few years ago I discovered a sketch book, discussed in my 2017 study Plautilla Bricci. Pictura et Architectura Celebris. L’architettrice del barocco romano, which gives us grounds for speculation. The taccuino (notebook) is enclosed in Benedetti’s last will; it includes both architectural drawings (figs. 2, 3 and 4) and technical notes referring to the renovation of Benedetti’s domus magna in via di Monserrato.

Between 1656 and 1658, Plautilla could reasonably have joined the enterprise as a young fellow of Cassiano dal Pozzo’s academy. The prelate had organized in his Palace in via dei Chiavari an intellectual circle, open to women artists such as Anna Maria Vaiani and Maddalena Corvini, whose members contributed to his Paper Museum. Dal Pozzo’s library inventory lists many architecture books, from manuals to the latest essays and studies of the day. These volumes indicate dal Pozzo’s pedagogical and didactical commitment to fill an educational void, since architecture classes were not offered in the course catalogue of Accademia di San Luca. Plautilla could have attended these classes, and could have practiced as a young architect in one of the many building sites of Rome.

Altarpieces, monuments, and a country villa

In 1660, Bricci painted the monumental altarpiece with The Birth of the Virgin (fig. 5), set in one of the side chapels of the Benedictine monastery of Santa Maria in Campo Marzio. The abbess there was Anna Maria Mazzarino, niece of the influential Cardinal Mazzarino. The painting is evidently inspired by Cavalier d’Arpino’s style and language; it closely resembles his work in the church of Santa Maria di Loreto.

When Mazzarino died in 1661, Plautilla, through Benedetti, was asked to prepare a drawing for his funeral ephemeral structures. The National Library in Turin preserves a folio with the illustration of the armor and the virtues of the powerful Secretary of State, accompanied by a moving inscription (figs. 6 and 7). In these drawings (front and back) Plautilla shows her expertise with Baroque language, exhibited here with sophistication and elegance.

Plautilla Bricci achieved recognition as architectrice celebris with the work she carried out at the Villa Benedetti, Elpidio Benedetti’s sumptuous residence outside the walls of Rome, and at the chapel of San Luigi.

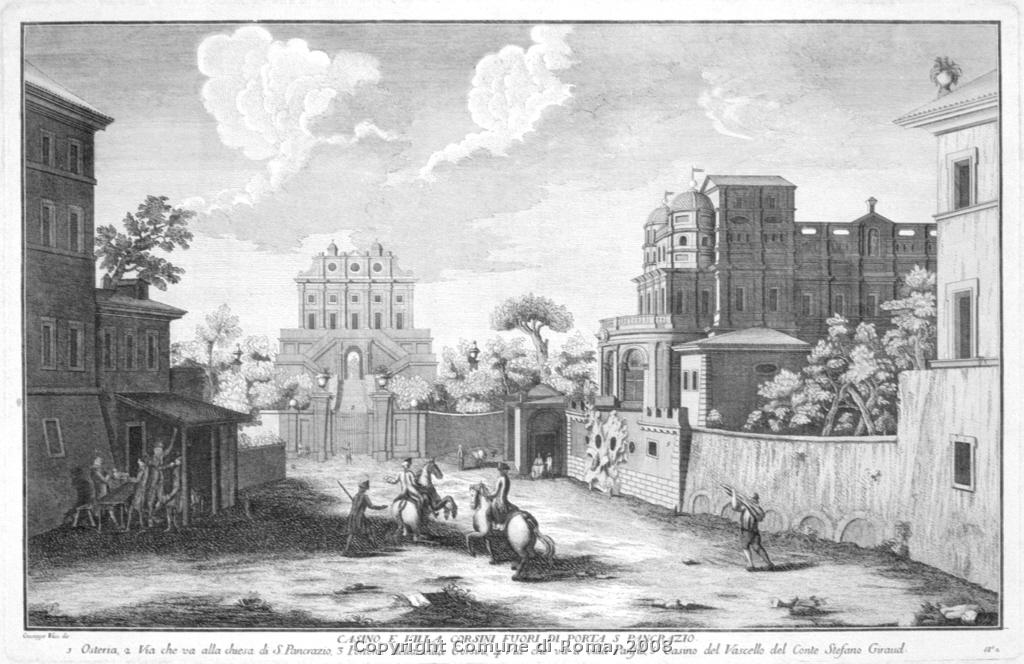

From 1663 to1668, Plautilla was committed to the ambitious project of Villa Benedetti (which was almost completely destroyed during the French siege of Rome in 1849). Giuseppe Vasi’s etching (fig. 8) shows the façade and the exterior of the building, which resembles that of a ship (hence the nickname of Vascello, “vessel”). There are seven surviving drawings which present the distribution of the interior, layer by layer. The Villa was an outstanding unicuumin the framework of the civil architecture of seventeenth-century Rome.

A major commission at Chiesa di San Luigi dei Francesi

The chapel of San Luigi, in the homonymous Chiesa di San Luigi dei Francesi (the church of the French Nation in Rome), is the veritable demonstration of her architectural talent. Building began in 1670, and was completed by 1680. Plautilla conceived and directed the overall design and execution of the project. She also painted the altarpiece with St. Louis between History and Faith (fig. 9), a monumental canvas she signed at the lower right edge as “Plautilla Bricci Romana Invenit.”

How she obtained this commission is obscure, and will probably be so forever, since the documents relating to the history of the chapel were destroyed by fire at the beginning of the nineteenth century. As a surmise, Plautilla could have been endorsed by Anne of Austria, the regent queen, who advocated both for women’s creativity and for the participation of women in public life, and who supported the opening of a female school in her Parisian court. Moreover, through this commission to a woman, the queen would have been able to complete the project undertaken by her mother-in-law, Marie de Medici, who promoted the foundation of the chapel.

Later life and works

In 1675, the canons of the Basilica of St. John Lateran appointed Plautilla to paint a lunettone with the Presentation of the Sacred Heart of Jesus (fig. 10).

She signed the monumental curved canvas, for which subject matter she invented new iconography. (It was later replaced by Pompeo Batoni’s painting, done for the Church of Jesus in Rome.) For the chapel of the Holy Sacrament at the Lateran, she completed two frescoes, a St. Dominique and a St. Francis, which were smashed down during the building’s renovation in the late nineteenth century.

Plautilla’s last documented activity took place in a small village, Poggio Mirteto, a Benedetti family enclave. On the occasion of the 1675 Holy Year, the congregation of the Oratory of St. John the Baptist commissioned her to create a processional standard (figs. 11/12) representing the birth (front) and the beheading of the John the Baptist (back), for which she was recompensed with 100 scudi. Subsequently Plautilla designed the sophisticated white-and-gold stucco bas-relief for the local Collegiate, which is considered to be her last masterpiece.

After that, information about Plautilla Bricci becomes ever more scant. In 1686 she presented a painting at the art show held in San Salvatore in Lauro, where she is designated as “Signora Plautilla,” in public recognition of her professional status.

In 1677 Plautilla and Basilio, her brother, moved to Borgo Nuovo di San Francesco a Ripa, to a house which, in his last will (of the 1690s), Elpidio Benedetti allowed her to enjoy (usufrucht, without altering) for the duration of her life (“vita natural durante”). In this document, he refers to Plautilla as “persona di età assai avanzata” (a very aged person).

Plautilla died on December 13, 1705 at the monastery of Santa Margherita in Trastevere, where she had moved in 1692 after Basilio passed away. She is buried in Santa Maria in Trastevere, next to her beloved brother.

Dr. Consuelo Lollobrigida is an art historian specializing in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Italian and French visual art. She completed her PhD in Art History at Sapienza University in 2008 with a thesis on women artists in Baroque Rome. She has served on the Faculty of Art History at the University of Arkansas Rome Center since 2012. She has given many presentations, internationally, about history’s women artists. Her books include Plautilla Bricci. Pictura et Architectura celebris. L’architettrice del Barocco Romano (Gangemi International, 2017); Following women artists. A Guide of Rome (EtGraphiae, 2013); and Maria Luigia Raggi. Il capriccio architettonico tra Arcadia e Grand Tour (Edizioni Budai, 2012).

More Art Herstory posts about Plautilla Bricci:

Plautilla Bricci: A Painter & “Architettrice” in Seventeenth-century Rome, by Alessandra Masu

More Art Herstory posts about Italian women artists:

Three Historic Women Artists Exhibitions: A Dispatch from Italy, by Alessandra Masu

Female Solidarity in Paintings of Judith and her Maidservant by Italian Women Artists, by Sivan Maoz

Roma Pittrice: Women Artists at Work in Rome Between the Sixteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, by Alessandra Masu

Maddalena Corvina’s Saint Catherine of Alexandria, by Kali Schliewenz

Stitching for Virtue: Lavinia Fontana, Elisabetta Sirani, and Textiles in Early Modern Bologna, by Patricia Rocco

Thoughts on Feminist Art History in the Wake of Artemisia: Vrouw & Macht at Rijksmuseum Twenthe, by Jitske Jasperse

The Restoration of Royalty: Lavinia Fontana’s Queen of Sheba and King Solomon, by Aoife Brady

By Her Hand: Personal Thoughts and Reflections on an Exhibition, by Oliver Tostmann

Sister Eufrasia Burlamacchi (Lucca, 1478–1548), by Loretta Vandi

In defense of monographic exhibitions of female artists: The case of Fede Galizia, by Camille Nouhant

Giovanna Garzoni’s Portrait of Zaga Christ (Ṣägga Krǝstos), by Alexandra Letvin

The Ladies of Art are in Milan, by Cecilia Gamberini

Celebrating Bologna’s Women Artists, by Babette Bohn

Drawings by Bolognese Women Artists at Christ Church, Oxford, by Jacqueline Thalmann

Lavinia Fontana and Elisabetta Sirani at the Smith College Art Museum, by Danielle Carrabino

Artemisia Gentileschi: What Wasn’t in the London Exhibition and Why it Matters, by Dr. Jesse Locker

Suor Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596–1676), Convent Artist, Guest post by Dr. Angela Ghirardi

Elisabetta Sirani of Bologna (1638–1665), Guest post by Dr. Adelina Modesti

Lavinia Fontana: Italy’s First Female Professional Artist, Guest post by Dr. Elizabeth Lev

“La grandezza del universo” nell’arte di Giovanna Garzoni / “The grandeur of the universe” in the art of Giovanna Garzoni (Guest post/review by Dr. Sara Matthews-Grieco)

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi (Guest post by Dr. Mary D. Garrard)

Sister Caterina Vigri (St. Catherine of Bologna) and “Drawing for Devotion” (Guest post by Dr. Kathleen G. Arthur)

Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596-1676), Convent Artist (Guest post by Dr. Angela Ghirardi)

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves (Guest post by Dr. Katherine A. McIver)

Rediscovering the Once-Visible: 18th-century Florentine Artist Violante Ferroni (Guest post by Dr. Ann Golob)

A Tale of Two Women Painters (Guest post by Natasha Moura)

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective (Guest post by Dr. Judith W. Mann)

Other Art Herstory blog posts you may enjoy:

The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian (Guest post by Prof. Emma Steinkraus)

Do We Have Any Great Women Artists Yet? (Guest post by Dr. Sheila ffolliott)

The Politics of Exhibiting Female Old Masters (Guest post by Dr. Sheila Barker)

Why Do Old Mistresses Matter Today? (Guest post by Dr. Merry Wiesner-Hanks)

New Adventures in Teaching Art Herstory (Guest post by Dr. Julia Dabbs)

Plautilla Bricci nowadays is recognized as an important artist of her time thanks to your job that has highlighted some points. Thank you Consuelo Lollobrigida always a great job!