Guest post by Camille Nouhant

The limitations of group exhibitions for women artists

Much has been done for female artists, ever since the pioneering exhibition organized by Linda Nochlin and Ann Sutherland Harris in 1976 at the Los Angeles County Museum. Much has been done, yet so little. A dozen books are now available in the shops of many museums, presenting a choice—often limited—of women in the arts, from the Renaissance to the modern day. Every month, we learn that yet another exhibition is set to open, focusing on “women artists.” Indeed, they are gaining space under the spotlight.

But there lies the issue: apart from Artemisia Gentileschi, whose life is much more discussed than her talent, how many women have been deemed worthy of a monographic exhibition? One could argue that some of them, like Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, are now well known by the public, and that thousands of derived objects featuring Frida Kahlo’s face exist nowadays, including table mats (yes, I own one). Yet, most of the women artists who lived prior to the nineteenth century are almost systematically exhibited in groups, which has the effect of diminishing each one’s particular upbringing, artistic environment, and specific career.

If in some cases there is only one painting we know of for a female artist, such as Claudia del Bufalo or Lucrezia Quistelli, there are other women for whom enough signed artworks are clearly identifiable today, such as those of Elisabetta Sirani, Ginevra Cantofoli, or the Volò sisters. This is not to criticize exhibitions that group female artists, for they did (and still do) open the public’s eyes on this matter. However, isn’t it about time that, instead of discovering yet another hidden part of Picasso’s production, we give a woman her chance to shine, on her own?

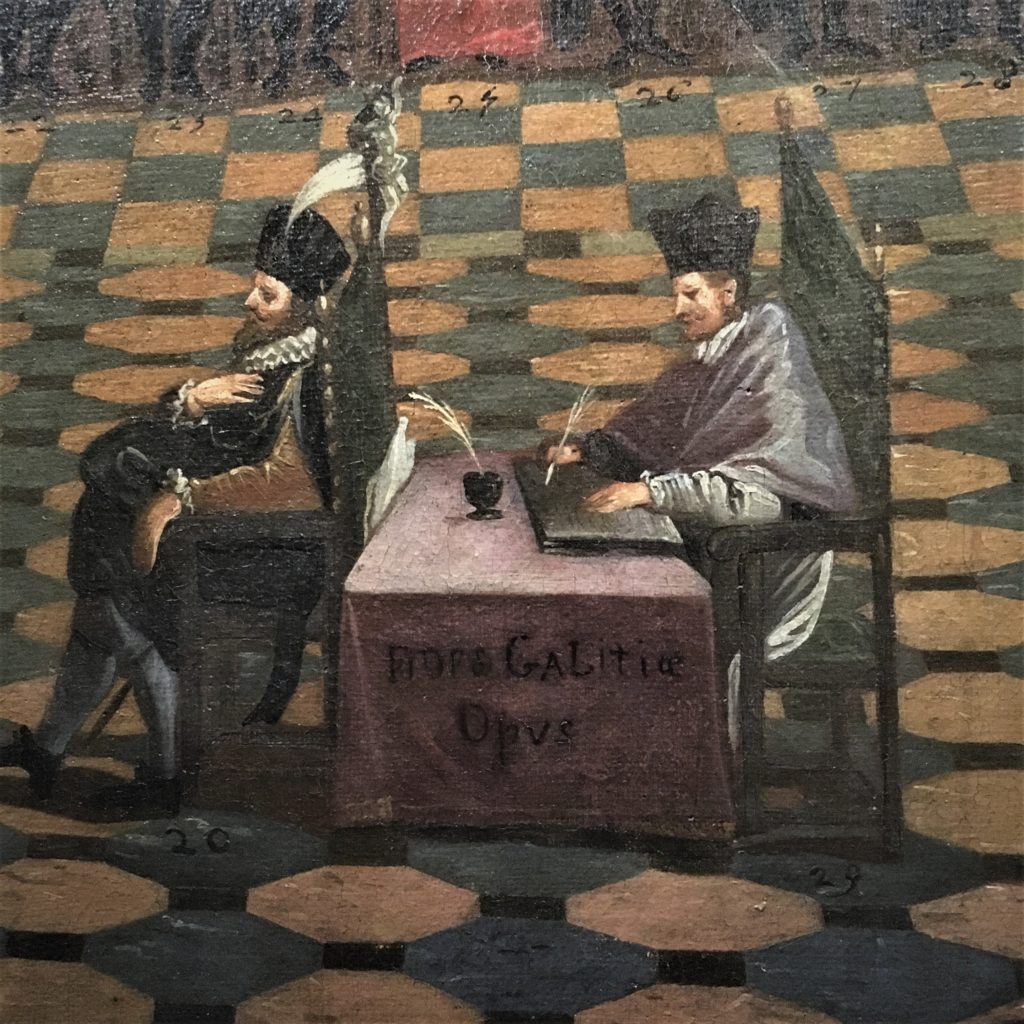

The Castello del Buonconsiglio in Trent (Italy) seems to have understood this necessity, for they just opened the first monographic exhibition dedicated to Fede Galizia.

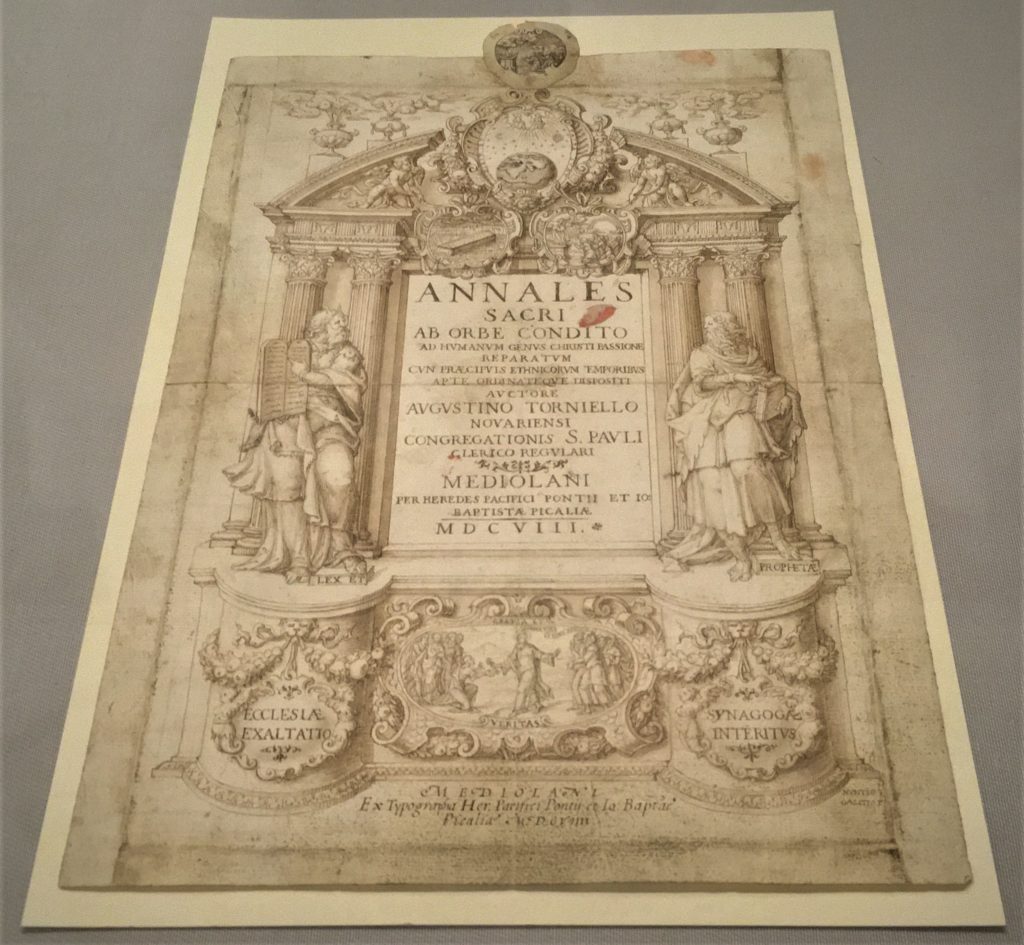

Fede Galizia, mirabile pittoressa was originally scheduled for the summer of 2020, but, for reasons we unfortunately know all too well, it was postponed. It finally opened on the evening of July 2—and needless to say, it was worth the wait. Curators Giovanni Agosti, Jacopo Stoppa, and Luciana Giacomelli chose to organize it in nine separate rooms, each focusing on a different aspect of Fede Galizia’s career. Agosti and Stoppa have worked together previously on exhibitions and publications dedicated to Lombard artists, while Luciana Giacomelli is a specialist in sacred art. The curators took it upon themselves to revisit Fede Galizia’s artistic production, which hasn’t been the subject of a catalogue raisonné since 1989.

Who is Fede Galizia ?

Before we dive further into the different facets of this event, it seems only fair that we answer the following question: Who was Fede Galizia? She was born in either Trent or Milan, between 1574 and 1578. Given her gender and the many problems Italian archives have faced throughout history, it is not an easy task to find any documentation regarding the painter and her life. Few records about her are available to us today, although the curators have managed, thanks to those few documents we do have, to recreate the potential genealogy of Fede Galizia. It seems like art ran in the family’s veins, and especially those of Nunzio, Fede’s father.

She learned painting, as well as probably engraving, from her father, a multi-talented artist known to have produced “paste muschiate” and other luxury objects for noblemen such as Vincenzo I Gonzaga. By the way, one of the highlights of this exhibition is a never-seen-before group of drawings signed and attributed to Nunzio Galizia.

An artistic celebrity in her time

The talent of Fede Galizia was such that by the end of the 1590s, many famous authors had praised her, among them Gian Paolo Lomazzo and Paolo Morigia. The latter even mentions the admiration for her of one of the most important figures of the time: Rudolf II. Indeed, Morigia explains that a few of her paintings were sent to the Holy Roman Emperor, thanks to the intervention of Giuseppe Arcimboldo. The historian and Jesuate informs us that Fede Galizia even received a prestigious commission to paint the portraits of the Queen and Infanta of Spain, Margaret of Austria and Isabella Clara Eugenia.

Not just a still life painter

Given this recognition by her contemporaries, it is even more difficult to understand how such a famous artist during her lifetime could have fallen into oblivion. Although she was never completely erased from the city guides of Milano or the stories of Lombard painting, by 1950, she would only be mentioned by Roberto Longhi for her still lifes. Interestingly enough, only one of Fede Galizia’s contemporaries alludes to this aspect of her oeuvre, while the vast majority of sources in which she is cited prior to the beginning of the nineteenth century praise her talent as a portraitist or as an altarpiece painter.

Thus, it appears that the disappearance of Fede Galizia from the historical record has less to do with her talent, recognized by major artists and collectors of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and more to do with how art history systematically chooses to present women as “flower painters.” Yes, Rachel Ruysch did make a (pretty decent) living out of still life paintings, but Fede Galizia’s work shouldn’t be reduced to it. The curators avoided doing such a thing, by highlighting her still lifes only at the very end of the Castello del Buonconsiglio exhibition.

Fede Galizia, mirabile pittoressa: structure and design

Indeed, they made it their priority to present every major aspect of Fede Galizia’s career. From her status as a female artist, to her rendering of the antisemitic cult around Simon of Trent, as well as her depiction of San Carlo Borromeo, the nine rooms offer a complex overview of her life. The different sections of the exhibition explore the following themes:

- Female artists of the time;

- Trent;

- Milan;

- Miniatures;

- Judith;

- The influence of Correggio and Parmigianino;

- Portraits;

- Altarpieces; and finally

- Still-lifes

Not only have the curators chosen to redefine the way we look at this painter, but they also wanted to place Fede Galizia in the context of her peers, featuring paintings and drawings by Sofonisba Anguissola, Giovanni Ambrogio Figino, Bernardo Buontalenti, Daniele Crespi and Jan Brueghel the Elder, to name only a few.

The design of the exhibition rooms, which clashes with the Renaissance ceilings of the Castello, came out of the mind of Alice de Bortoli, who decided to wrap the artworks in metallic curtains. One might not enjoy this type of “modern” installation, but this system creates a sort of bubble around the paintings, allowing the visitor to focus solely on the exhibition and not the surroundings.

However, the scenography is particularly relevant when it comes to the Judith and altarpiece rooms. Although they are not mentioned by her contemporaries, Fede Galizia seems to have encountered fame partly thanks to her Judith, a prominent subject for painters during the Counter-Reformation. For the first time, the Castello del Buonconsiglio offers to the public four of the known versions, facing an interpretation by Lavinia Fontana of the same subject.

As for the altarpieces, the Noli me tangere stands out, with its size of 3 by 2 meters, demonstrating that Fede Galizia’s production covers a varied spectrum, and is deserving of more attention. The last altarpiece, San Carlo in Procession with the Holy Nail, offers a glimpse of Fede Galizia’s death, in 1630, for the painter probably succumbed to the “manzoniana” plague.

The lasting achievements of Fede Galizia

The case of Fede Galizia provides sufficient evidence that a woman artist should be considered first and foremost as an artist, rather than suffering disdain due to her gender. Not only did she portray sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Milan, but she also was respected enough to receive prestigious commissions from churches and from many crowned heads. The exhibition at the Castello del Buonconsiglio is surely only the beginning of many (re)discoveries…

Camille Nouhant is an art history student, and is currently finishing her master’s thesis on Fede Galizia, at the Sorbonne (Paris IV).

Fede Galizia, mirabile pittoressa at Castello del Buonconsiglio, Trent (Italy), runs July 3–October 24, 2021. Online reservation is mandatory.

More Art Herstory exhibition reviews:

Roma Pittrice: Women Artists at Work in Rome Between the Sixteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, by Alessandra Masu

Making Her Mark Leaves its Mark at the Art Gallery of Ontario, by Isabelle Hawkins

Female Artists and their Remarkable Careers: An Appeal to Rethink Art History, by Jenny Körber

Early Modern European Women Artists at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, by Erika Gaffney

Making Her Mark, An Essential Corrective in the History of Art, by Chadd Scott

Reflections on Making Her Mark at the Baltimore Museum of Art, by Erika Gaffney

Masters and Sisters in Arts, by Jitske Jasperse

Sofonisba Anguissola in Holland, an Exhibition Review, by Erika Gaffney with Cara Verona Viglucci

Sofonisba Anguissola: Portraitist of the Renaissance at Rijksmuseum Twenthe, by Nelleke de Vries

Judith’s Challenge, from Lavinia Fontana to Artemisia Gentileschi, by Alessandra Masu

Anna Dorothea Therbusch: A Woman Painting Against Eighteenth-century Odds, by Stephanie Pearson

Thoughts on By Her Hand, the Hartford Iteration, by Erika Gaffney

Plautilla Bricci: A Painter & “Architettrice” in Seventeenth-century Rome, by Alessandra Masu

Thoughts on Feminist Art History in the Wake of Artemisia: Vrouw & Macht at Rijksmuseum Twenthe, by Jitske Jasperse

By Her Hand: Personal Thoughts and Reflections on an Exhibition, by Oliver Tostmann

The Ladies of Art are in Milan, by Cecilia Gamberini

“Artemisia” at the National Gallery: A Review, by Dr. Sheila McTighe

“La grandezza del universo” nell’arte di Giovanna Garzoni / “The grandeur of the universe” in the art of Giovanna Garzoni, by Dr. Sara Matthews-Grieco

Warp and Weft: Women as Custodians of Jewish Heritage in Italy, by Dr. Anastazja Buttitta

Women Artists of the Dutch Golden Age at the National Museum of Women in the Arts

A Tale of Two Women Painters, by Natasha Moura

Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists, by Dr. Elizabeth Sutton

‘Bright Souls’: A London Exhibition Celebrating Mary Beale, Joan Carlile, and Anne Killigrew, by Dr. Laura Gowing

More posts about Italian women artists:

The Restoration of Royalty: Lavinia Fontana’s Queen of Sheba and King Solomon, by Dr. Aoife Brady

By Her Hand: Personal Thoughts and Reflections on an Exhibition, by Oliver Tostmann

Sister Eufrasia Burlamacchi (Lucca, 1478–1548), by Dr. Loretta Vandi

Giovanna Garzoni’s Portrait of Zaga Christ (Ṣägga Krǝstos), by Dr. Alexandra Letvin

Artemisia Gentileschi: What Wasn’t in the London Exhibition and Why it Matters, by Dr. Jesse Locker

“I feel again the violence of a curious desire”: Rare client testimonies on Rosalba Carriera’s erotic art, Guest post by Dr. Angela Oberer

Plautilla Bricci (1616–1705): A Talented Woman Architect in Baroque Rome, Guest post by Dr. Consuelo Lollobrigida

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi, Guest post by Dr. Mary D. Garrard

Sister Caterina Vigri (St. Catherine of Bologna) and “Drawing for Devotion,” Guest post by Dr. Kathleen G. Arthur

Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596–1676), Convent Artist, Guest post by Dr. Angela Ghirardi

Rediscovering the Once Visible: Eighteenth-Century Florentine Artist Violante Ferroni, Guest post by Dr. Ann Golob

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves, Guest post by Dr. Katherine McIver

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective, Guest post by Dr. Judith W. Mann

Trackbacks/Pingbacks