Guest post by Emma Steinkraus, Assistant Professor of Fine Arts, Hampden-Sydney College

Two of my favorite seventeenth-century women artists, Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian, were also excellent naturalists. As I combed through their paintings and prints this year, I discovered depictions of insects that struck me as unusual. While their male peers treated insects as symbols in still lives or as dead specimens to be catalogued, Garzoni and Merian instead represented insects as sympathetic subjects. This interested me because their portraits of insects emerged during a century of crucial entomological discoveries, many of which upended popular misconceptions about gender. I wondered, could the discovery of insect matriarchies, like beehives, have found an especially receptive audience in these two exceptional women? And is it possible that their understanding of gender was, in turn, influenced by the insects they studied?

Unconventional Lives

I was intrigued because both Garzoni and Merian lived unconventional lives for women at the time. Both tossed off the strictures of marriage, travelled widely, and built successful art careers.

Giovanna Garzoni was born in 1600 in the Marche region of Italy. She married the moody Venetian painter Tiberio Tinelli, but quickly precured an annulment and was known as “Chaste Giovanna” ever after. She was in high demand for her proto-pointillist paintings and served patrons across Europe in Florence, Venice, Rome, Naples, Paris, and possibly London. During her life, her paintings commanded “any price that she asked.”

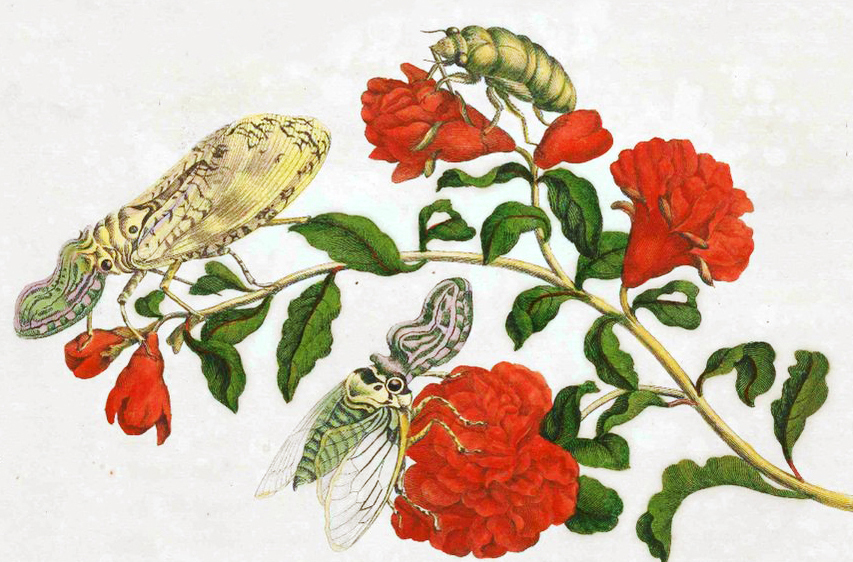

Maria Sibylla Merian was born in Germany in 1647. Like Garzoni, she married a fellow artist, but in her late thirties she left her husband and moved into an anti-hierarchical Labadist commune in a castle with her mother and two daughters. While there, Merian saw a shipment of insects from what was then the Dutch colony of Suriname. She was mesmerized. In 1699, at the age of fifty-eight, she auctioned off her studio and set sail. For two years, she explored the Surinamese jungle, documenting its flora and fauna. Her engravings revolutionized scientific illustration. Her innovation was to collect and observe living creatures, rather than dead ones. She was the first artist to depict the entire life cycle of an insect, its characteristic behaviors, and its habitat, all within the same image. Her work is to her predecessors’ what the diorama is to the shadow box.

Insects in the Seventeenth Century

In most seventeenth-century representations, insects functioned as symbols in still lives, or as objects for scientific scrutiny. Willem Van Aelst, who overlapped with Garzoni in Rome and with Merian in Amsterdam, provides a good example of the use of insects as symbols. The white butterfly suggests the fragility of life, while the fly is a reminder of the imminence of decay.

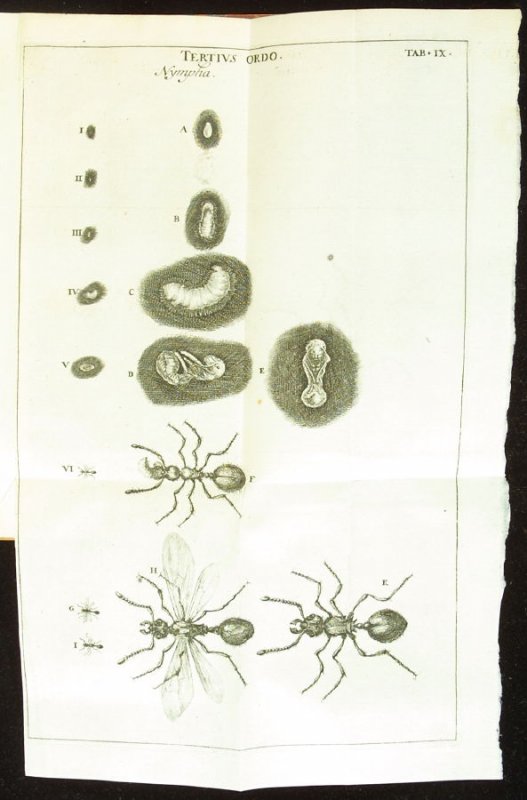

In the scientific illustrations of the seventeenth century, insects were not symbols, but neither were they subjects. They were objects, laid out in labeled rows, dead and often dissected. The goal of these images was the taxonomic organization of organisms, exemplified here by the work of Jan Swammerdam.

Public domain.

A Break from Tradition

Within this context, Merian and Garzoni’s insect paintings were a striking departure. Merian’s images bristle and swarm with activity. Plants and insects form their own calligraphy, spiraling into curlicues of tendril, tongue, and tail. Her insects are animated protagonists participating in incredible dramas. She was the first to depict leaf-cutter ants defoliating trees, ants building bridges, and spiders eating birds. Kay Etheridge writes that Merian was the first to describe the “life cycles of insects along with their plant hosts” and the “first to emphasize interactions among the species portrayed,” observations that form “the very foundation of the study of ecology.”

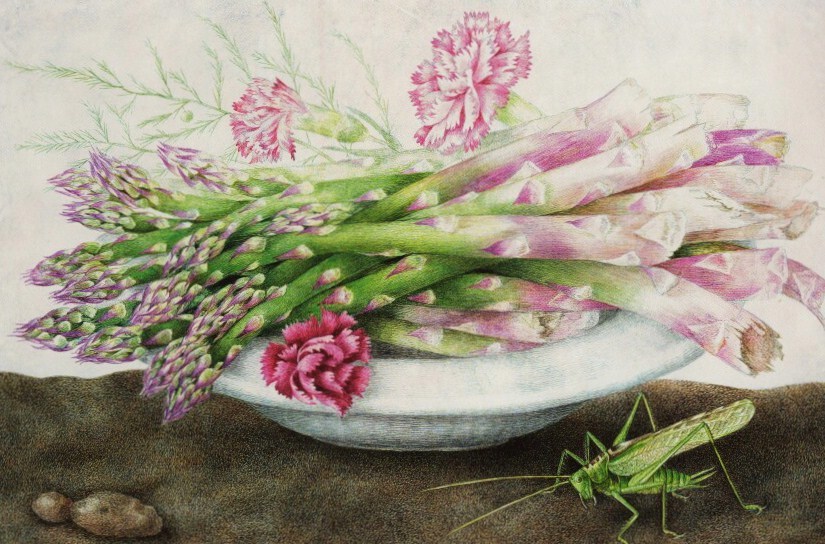

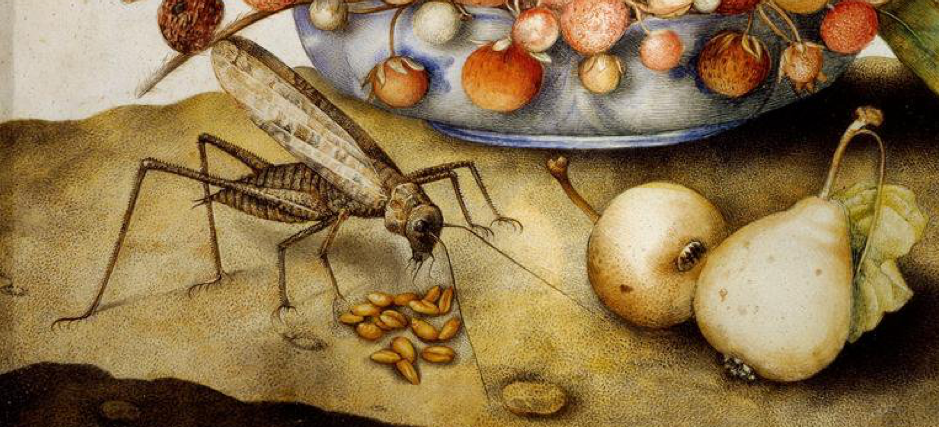

Garzoni also depicted insects as protagonists. The insects in her paintings are lively characters who seem to meet our gaze. While Garzoni’s work is best categorized as still life, she too participated in the birth of modern science, illustrating a herbarium and adding to the documentation of the Medicis’ extensive botanical and zoological collections.

gouache on vellum. Galleria Palatina, Florence.

In the work of both women, insects frequently meet the eye of the viewer. Their work displays what Donna Haraway calls an “intersecting gaze” of reciprocity across species. Where the insects look away, they remain active and animated. Plants, too, appear lively and decisive. The morning glory below, for example, reaches out, defying gravity, on the hunt for something. All living things appear as actors.

The Subversive Potential of Matriarchal Insects

My hunch is that Merian and Garzoni’s sensitivity to insects was influenced by their position as women. Despite their foundational roles in ecology, insects were commonly overlooked, underestimated, and marginalized. Yet the seventeenth-century revelation that many insects lead matriarchal lives upended conventional understandings of gender.

In 1609, Charles Butler published The Feminine Monarchie, arguing that the head of the beehive was not a king, as had been thought, but a queen. This discovery provoked a crisis in the understanding of gender across Europe. “Much of the collective energy of the next two centuries,” writes Frederick Prete, “was spent trying to reconcile the emerging seemingly anomalous discoveries of entomologists with socially acceptable metaphors about sovereignty, class, and gender roles.”

These observations had a special authority because in the seventeenth century, observing nature was seen as a way of honoring God. Creation was the “second Bible”—and each creature in it, a letter or a page. As a result, seventeenth-century entomological discoveries had real subversive potential. If God expressed himself through creation, and creation in the form of a beehive revealed a highly-productive and well-organized society of women who killed all the men each winter and were ruled over by a promiscuous queen, what exactly was God trying to say? But if insect matriarchies disturbed men, might they have equally inspired and motivated women?

tempera and watercolor on vellum. Villa Poggio a Caiano, Italy.

Certainly, Garzoni often included matriarchal insects like bees and wasps in her work. Her still lives include bumblebees, yellowjackets, and carpenter bees, who live in small matriarchal groups.

Merian also depicted bees and social insects. And she clearly knew the gender of many of her subjects. In the first plate of Der Raupen, for example, she shows a large female silk moth laying eggs next to the smaller male.

Radical Entomologists

Could it have been that in practicing a reciprocal gaze, Merian and Garzoni not only depicted insects differently, but also found a model for their own unconventional lives and personal transformations? Perhaps the most fascinating evidence that insects could open up radical channels of thought comes from Merian’s contemporary, the entomologist Jan Swammerdam.

Like Merian, Swammerdam joined a heterodox Protestant sect with a female spokesperson. (In Swammerdam’s case, the spokesperson was the complex mystic Antoinette Bourignon; in Merian’s case, she was Bourignon’s compelling rival, Anna Maria van Schurman.) Swammerdam’s writing connects his egalitarian views with his studies of insects. “There is no superiority or pre-eminence,” he writes, “among either Bees or Ants; love and unanimity, more powerful than punishment or death itself, presides there, and all live together in the same manner as the primitive christians [sic] anciently did, who were connected by fraternal love, and had all things in common.”

Perhaps in studying insects, Merian and Garzoni found support and inspiration for the highly unusual lives they led as single women, artists, naturalists, and travelers. For me, their adventurous lives and the discovery of insect matriarchies in the seventeenth century are tantalizing evidence of a connection between early entomology and protofeminism. The study of insects disrupted widespread belief in the naturalness of male superiority, encouraged the contemplation of personal metamorphosis, and revealed complex societies dominated by women.

In the modern era, many women have explicitly found inspiration in insects. Feminist writers like Charlotte Perkins Gilman and Octavia Butler have constructed science fiction inspired by entomology, while theorists like Barbara Creed have argued that insects represent “monstrous-feminine bodies” that threaten the masculine order.

By studying Garzoni and Merian in the light of entomological history—and in light of these later examples and theories—I wonder if we might find subversive prototypes for more egalitarian, feminist, and ecological ways of seeing.

Professor Emma Steinkraus is a visual artist and assistant professor at Hampden-Sydney College. Her paintings explore gender, ecological collapse, and history through an idiosyncratic, personal lens. Her current project mines archives to document the contributions of overlooked early modern female artist-naturalists. Her work can be found online at www.emmasteinkraus.com and @emmasteinkraus.

Visit Art Herstory’s Giovanna Garzoni resource page, here.

Visit Art Herstory’s Maria Sibylla Merian resource page, here.

More Art Herstory blog posts about natural history illustration:

Women and the Art of Flower Painting, by Ariane van Suchtelen

Barbara Regina Dietzsch: Enlightened Flower Painter, by Andaleeb Badiee Banta

Madeleine Françoise Basseporte’s Hyacinths at the French Court, by Mary Creed

Curiosity and the Caterpillar: Maria Sibylla Merian’s Artistic Entomology, by Dr. Kay Etheridge

Alida Withoos: Creator of beauty and of visual knowledge, by Catherine Powell

Women in Zoological Art and Illustration (Guest post by Ann Sylph, Librarian of the Zoological Society of London)

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

Louise Moillon: A pioneering painter of still life, by Lesley Stevenson

Rachel Ruysch’s Vase of Flowers with an Ear of Corn, by Lizzie Marx

The Restoration of Royalty: Lavinia Fontana’s Queen of Sheba and King Solomon, by Dr. Aoife Brady

Sister Eufrasia Burlamacchi (Lucca, 1478–1548), by Dr. Loretta Vandi

Giovanna Garzoni’s Portrait of Zaga Christ (Ṣägga Krǝstos), by Dr. Alexandra Letvin

In defense of monographic exhibitions of female artists: The case of Fede Galizia, by Camille Nouhant

The Ladies of Art are in Milan, by Dr. Cecilia Gamberini

“Artemisia” at the National Gallery: A Review, by Dr. Sheila McTighe

Artemisia Gentileschi: What Wasn’t in the London Exhibition and Why it Matters, by Dr. Jesse Locker

Plautilla Bricci (1616–1705): A Talented Woman Architect in Baroque Rome, Guest post by Dr. Consuelo Lollobrigida

“Artemisia” at the National Gallery: A Review, Guest post by Dr. Sheila McTighe

“I feel again the violence of a curious desire”: Rare client testimonies on Rosalba Carriera’s erotic art, Guest post by Dr. Angela Oberer

“La grandezza del universo” nell’arte di Giovanna Garzoni / “The grandeur of the universe” in the art of Giovanna Garzoni (Guest post/review by Dr. Sara Matthews-Grieco)

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi (Guest post by Dr. Mary D. Garrard)

A Clara Peeters for the Mauritshuis, by Dr. Quentin Buvelot

Floral Still Life, 1726—A Masterpiece by Rachel Ruysch, by Dr. Lawrence W. Nichols

Women Artists of the Dutch Golden Age at the National Museum of Women in the Arts

Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser: Founding Women Artists of the Royal Academy

Gesina ter Borch: Artist, not Amateur (Guest post by Dr. Nicole E. Cook)

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective (Guest post by Dr. Judith W. Mann)

New Adventures in Teaching Art Herstory (Guest post by Dr. Julia Dabbs)

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves (Guest post by Dr. Katherine A. McIver)

A Dozen Great Women Artists, Renaissance and Baroque

Why Do Old Mistresses Matter Today? (Guest post by Dr. Merry Wiesner-Hanks)

“While their male peers treated insects as symbols in still lives or as dead specimens to be catalogued, Garzoni and Merian instead represented insects as sympathetic subjects. ” Not quite. Garzoni and Merian’s contemporary Jan van Kessel the Elder is a nice counter-example. Stereotyping men should be avoided, I would think, as much as stereotyping women.

Thanks for the thoughtful reply, Chris. I agree with your critique, and think a more accurate sentence would start “While their male peers largely treated insects…” Jan van Kessel the Elder is a wonderful example of a male artist who looked at insects with immense sympathy.