Guest post by Mary D. Garrard, American University (Emerita)

In spring 2020, two female Old Master solo exhibitions would have occurred simultaneously: Artemisia Gentileschi, at the National Gallery, London, and Giovanna Garzoni, at Palazzo Pitti in Florence. The coronavirus has disrupted that coincidence. “Artemisia” has been postponed, as has “‘The Greatness of the Universe’ in the Art of Giovanna Garzoni,” to unknown future dates. This would have been a particular kind of milestone at a high tide for female artist exhibitions. Unlike Sofonisba Anguissola and Lavinia Fontana, who were conjoined in a recent show at the Prado, but had no personal connection with one another, Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi shared patrons and supporters—and they were very likely friends.

The Gentileschi-Garzoni relationship is a rare instance of a known personal connection between two early modern women artists. Unlike women writers in the same period, such as Lucrezia Marinella and Anna Maria van Schurman, whose texts and treatises include references to other women writers and document their sense of a female intellectual community, women artists in early modern Europe did not have female communities. (An exception was Bologna, which boasted a phenomenal number of women artists.) What they thought of their female artist contemporaries and predecessors has been rarely if ever recorded, though it can sometimes be inferred from their art.

Garzoni and Gentileschi were two of a kind. Anomalous as female artists in a masculine art world, they undoubtedly experienced gender injustice (Artemisia writes of it). Yet they were the most successful female artists of their generation, which followed that of Fontana and Anguissola. Both enjoyed the support of high-level patrons, and many of the same ones: Medici rulers in Florence, the Spanish viceroy in Naples, the Duchess of Savoy, King Philip IV of Spain, and King Charles I and Queen Henrietta Maria of England. Responding to the calls of patronage, the two artists traveled across Europe in precisely parallel movements. This has suggested to scholars the possibility of a close personal relationship (Garrard, 1989; Bissell, 1999, Barker, 2020).

Florence, Rome and Venice

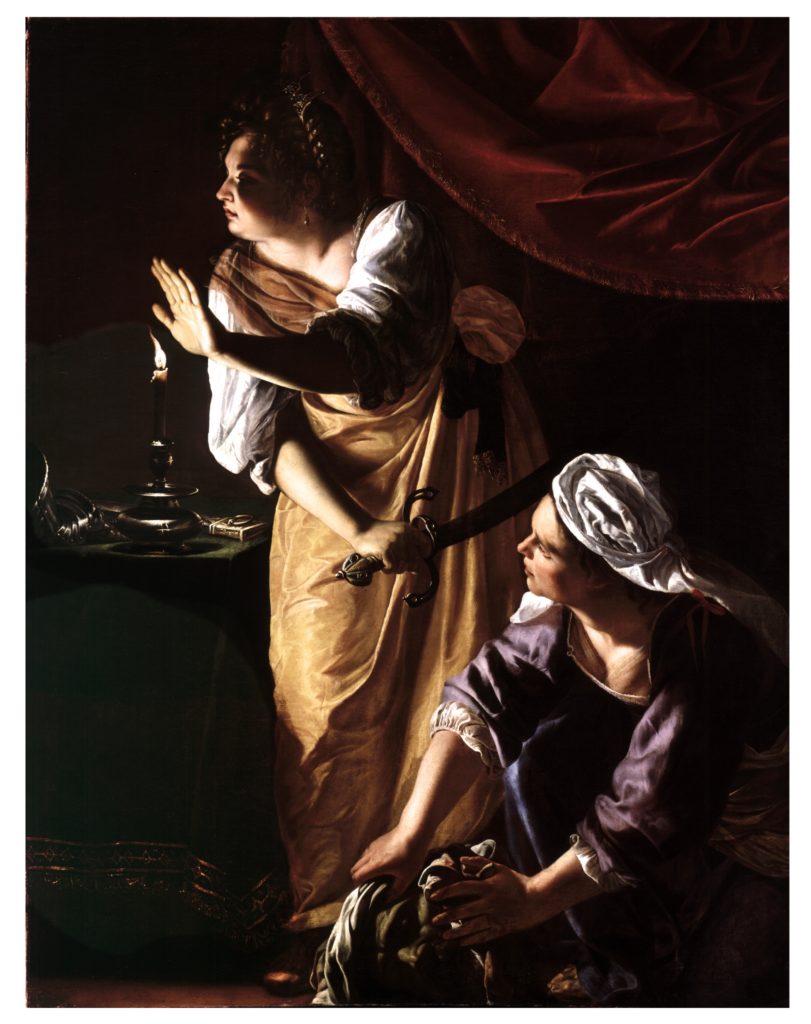

Artemisia Gentileschi and Giovanna Garzoni probably first met at the Medici court in Florence, a sparkling center of cultural activity nominally ruled by Grand Duke Cosimo II, but shaped and directed by his wife, Grand Duchess Maria Maddalena. When Giovanna, a fledgling young artist (seven years Artemisia’s junior), visited the Medici court sometime between 1618 and 1620, Artemisia was already a fixture there, painting such eye-opening pictures as the Uffizi Judith and the Self-portrait as a Lute Player.

One of Garzoni’s earliest known works, her Self-portrait as Apollo, was probably modeled on Artemisia’s depiction of herself with a musical instrument (Barker, 2020).

In the early 1620s, Artemisia was broadening her reputation as a painter (on a medal struck in her honor, she is called ‘pictrix celebris’), and continuing to produce large paintings of heroic women.

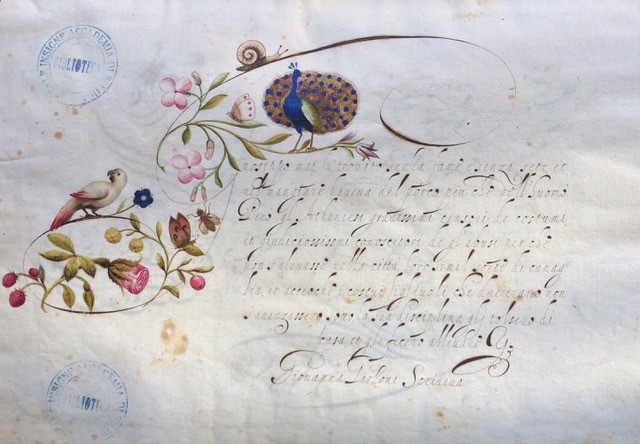

Garzoni took her talent in a different direction, developing a skill in calligraphy and sending samples to prospective patrons, in which exquisite lettering is decorated with lively drawings of birds, flowers, and insects.

The two artists overlapped again in Venice. Garzoni is documented there in 1625, and Gentileschi followed in 1626. They both left Venice in the spring of 1630, very likely to escape the plague that swept northern Italy that summer and would eventually kill over 46,000 people in Venice alone.

Naples, Turin, London, Paris

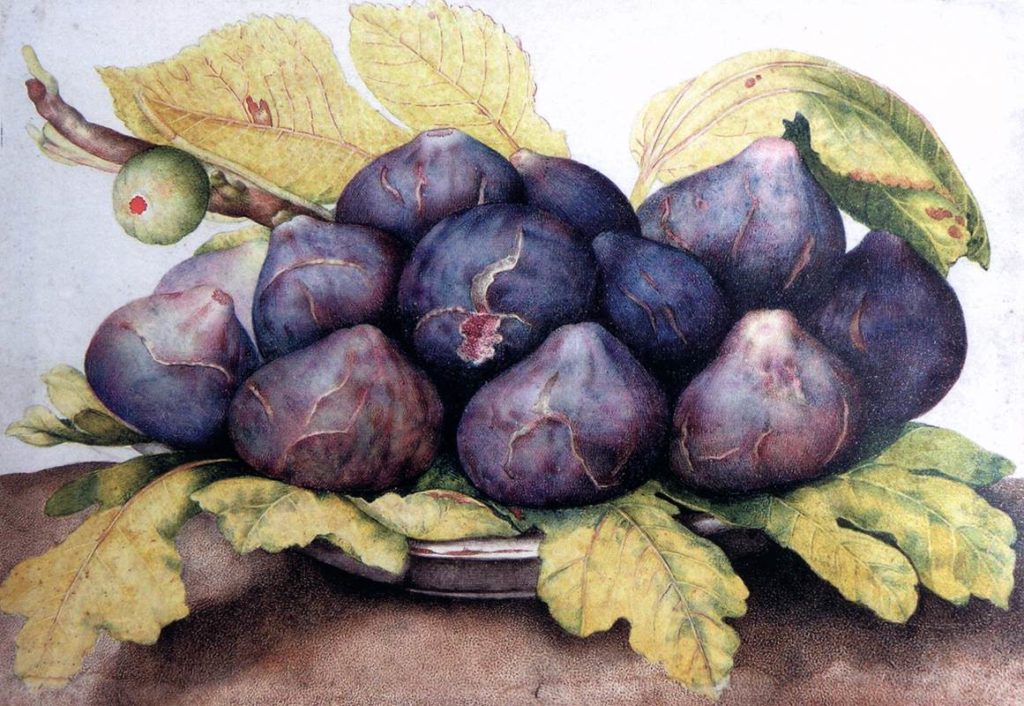

Garzoni and Gentileschi traveled from Venice to Naples, perhaps together, as each went to serve the Spanish viceroy in Naples, the duke of Alcalá. (For protection, both women often traveled accompanied by a brother; traveling in larger groups might have provided more security.) Artemisia may have paved the way for Giovanna, since Alcalá had previously bought paintings from her in Rome. Artemisia remained in Naples through most of the 1630s, working for the Spanish viceregal court and other patrons. After a year in Naples, Giovanna departed, first to Rome and then to Turin, where she served the duke and duchess of Savoy from 1632 to 1637, producing the fruit and flower still-life paintings that are the heart of her oeuvre.

In the mid-1630s, when Artemisia accepted Charles I’s repeated invitations to come to London, she was granted safe passage through France by the Savoy duchess Christine of France. This critical assistance (France was then enemy territory) may have been arranged for her by Garzoni. But when Artemisia went to London, so did Giovanna, and they likely traveled together from Turin.

Artemisia spent the years 1638–40 in London, working for Queen Henrietta Maria to complete the ceiling painting at the Queen’s House in Greenwich, begun by her father Orazio. Giovanna may also have served the Stuart court (she copied a drawing in the collection of the queen’s architect, Inigo Jones), but in 1640–41 she was in Paris, longing to return to Italy. This she did, and from 1642 to 1651, Garzoni was in Florence, working for Grand Duke Ferdinando II de’ Medici. Artemisia, who conceivably went with Giovanna to Paris, is documented again in Naples in 1642. From this point on, the two artists pursued separate professional opportunities, Giovanna serving another Medici court in Florence, and Artemisia resuming her career in Naples, where she would remain the rest of her life. Giovanna spent her final years in Rome, where she was an honored (albeit honorary) member of the Accademia di San Luca.

A relationship viewed through art

As two of a kind, Gentileschi and Garzoni experienced and negotiated the world in similar ways, and their lives were linked. What was the nature of this relationship? Was it primarily a utilitarian collaboration, or a friendship strengthened by mutual assistances? Were they competitive, envying the other’s successes? Or did they compete productively (a theory of competition that runs through Vasari’s lives of Renaissance artists), one artist inspired to strive for excellence by the example of another? Without further evidence, we cannot know. Yet the evidence of art suggests that these two female painters, prominent in the same patronage circles, might each have been spurred to clarify her unique artistic identity through sharp contrast with the other.

The two early self-portraits as musicians (shown above) are a case in point. Artemisia’s example of role-playing must have appealed to Giovanna, yet she adapted Artemisia’s prototype to her own very different personality. Gentileschi’s self-presentation as a gypsy lute player, which deliberately evokes her role in a contemporary performance, was a highly theatrical image, announcing itself as but one of the artist’s identities. (In a contemporaneous self-portrait, she depicted herself as an Amazon.) Artemisia’s emphasis on her highlighted bosom is provocative and daring, challenging any viewer who would take this playful self-sexualizing as the artist in toto (Garrard, Artemisia, 2020). Giovanna painted herself as Apollo, god of music, holding a stringed instrument she reputedly played; whereas Artemisia’s lute-playing is probably fictive. Garzoni’s self-portrait is Apollonian in other respects: she appears sober and serious, cool and rational. With Apollo’s power of prophecy, she seems intent on her own future and the recognition to come, already fantasized in the laurel wreath of fame. Against Artemisia’s complex mixture of identity traits—her turban is multiply allusive—Giovanna’s self-image is direct and straightforward.

Science and art

Gentileschi and Garzoni were acquainted with men who made dramatic breakthroughs in science. In Florence, Artemisia befriended the astronomer and physicist Galileo Galilei. Giovanna might have met Galileo at the Florentine court, for she alluded to him in a dedication to the Grand Duchess. In Rome, both artists were supported by Cardinal Francesco Barberini and Cassiano dal Pozzo, major collectors of art, scientific materials, and natural history. The more scientifically oriented Garzoni probably had further contacts with the Accademia dei Lincei, an important scientific community whose members included Galileo, Barberini and dal Pozzo. Her studies of individual plants and insects resemble the botanical drawings made by the Linceans, and were motivated by a similar desire to understand nature through close study and depiction of natural forms, aided by the newly invented microscope.

We can imagine that Artemisia, the painter of large-scale history pictures, might have scorned Giovanna’s painstakingly detailed depiction of little things. Her taste was for the larger world of dramatic action, and heroic deeds by women. Yet she understood the importance of Galileo’s discoveries. The precise arcs of spurting blood in the Uffizi Judith mirror the parabolic trajectory discovered by Galileo (Topper and Gillis, 1996)—a nod to accuracy that Giovanna might have approved (while perhaps disdaining the violence).

But Artemisia put Galileo’s science to poetic use. The dramatic curved shadow that overlays the Detroit Judith’s head echoes Galileo’s drawings of the moon’s phases—an astronomical allusion to the moon goddess Artemis, the painter’s namesake (Garrard, 1989).

Playful dispositions

Despite their differences, Giovanna and Artemisia shared certain sensibilities, the kind that can flourish in the conversations of friends. Throughout her oeuvre, each artist recurrently puts herself in the picture. Artemisia does this overtly, infusing her female characters with her presence, and sometimes her visage. Her personal identification with Lucretia, the ancient Roman rape victim, needs no explanation.

Garzoni, whose characters are vegetal, not human, includes herself in a different way. Her fruit suggests bodily associations—the plump peaches resemble female breasts and buttocks—and her still-life objects often behave anthropomorphically.

A split peapod reveals its peas, like a mouth opening to expose teeth, while five scattered peas sit by attentively, as if watching a performance.

In Garzoni’s miniature theater, insects are protagonists (as Emma Steinkraus noted in a related post on this site), and tiny objects mimic human behavior. All these are playful alter-egos through which the artist makes her presence known (Garrard, “Garzoni,” 2020).

As the last example shows, Garzoni had a sly sense of humor, and so did Gentileschi, who also infused her art with visual jokes. The Pitti Magdalene she painted for the Florentine Grand Duchess mocks the stereotype of the penitent saint.

Artemisia exaggerates the lachrymose gaze and gives the aristocratic woman a clumsy, hammer-toed foot, to pure comic effect (Garrard, Artemisia, 2020). The intended audiences for Artemisia and Giovanna’s playful pictures were not necessarily their patrons (the Grand Duchess who commissioned the Magdalene must have taken it straight). More likely, they injected whimsy to please themselves. Or perhaps it was each other.

Dr. Mary D. Garrard is Professor Emerita of Art History, American University (Washington, DC). She is the author of the first book on Artemisia Gentileschi (Artemisia Gentileschi: The Image of the Female Hero in Italian Baroque Art (Princeton University Press, 1989) and, most recently, Artemisia Gentileschi and Feminism in Early Modern Europe (Reaktion Books, 2020). This book is available now as an ebook; the hardcover edition will be available as of September 2020.

Mary’s essay, “The Not-So Still Lifes of Giovanna Garzoni,” appears in Sheila Barker, ed. and contributor, “The Immensity of the Universe” in the Art of Giovanna Garzoni, exh. cat., Florence, 2020. Garrard’s other publications include Brunelleschi’s Egg: Nature, Art and Gender in Renaissance Italy (University of California Press, 2010), and writings on Michelangelo, Sofonisba Anguissola and others. With Norma Broude, Garrard created and edited four volumes of essays in feminist art history that have been basic texts in art history and women’s studies courses. She serves on the editorial board of Illuminating Women Artists, a book series published by Lund Humphries, in which the initial volumes are due to appear in 2021.

Also cited here:

David Topper and Cynthia Gillis, “Trajectories of Blood: Artemisia Gentileschi and Galileo’s Parabolic Path,” Woman’s Art Journal, 17 (1996), pp. 10-13

R. Ward Bissell, Artemisia Gentileschi and the Authority of Art (Penn State, 1999)

Interested in learning more about these artists? Visit the Art Herstory Artemisia Gentileschi resource page and the Giovanna Garzoni resource page!

If you liked this Art Herstory guest blog post, you might also enjoy:

Three Historic Women Artists Exhibitions: A Dispatch from Italy, by Alessandra Masu

Early Modern Women Artists at Auction in 2025, by Erika Gaffney

Female Solidarity in Paintings of Judith and her Maidservant by Italian Women Artists, by Sivan Maoz

Plautilla Nelli and the Restoration of her Altarpiece Madonna del Rosario. by Jane Adams

Roma Pittrice: Women Artists at Work in Rome Between the Sixteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, by Alessandra Masu

Maddalena Corvina’s Saint Catherine of Alexandria, by Kali Schliewenz

Exhibiting Artemisia Gentileschi; From the Connoisseur’s Collection to the Global Museum Blockbuster, by Christopher R. Marshall

Portrayals of Mary Magdalene by Early Modern Women Artists, by Diane Apostolos-Cappadona

Judith’s Challenge, from Lavinia Fontana to Artemisia Gentileschi, by Alessandra Masu

Stitching for Virtue: Lavinia Fontana, Elisabetta Sirani, and Textiles in Early Modern Bologna, by Dr. Patricia Rocco

Thoughts on By Her Hand, the Hartford Iteration, by Erika Gaffney

Plautilla Bricci: A Painter & “Architettrice” in Seventeenth-century Rome, by Alessandra Masu

Thoughts on Feminist Art History in the Wake of Artemisia: Vrouw & Macht at Rijksmuseum Twenthe, by Jitske Jasperse

The Restoration of Royalty: Lavinia Fontana’s Queen of Sheba and King Solomon, by Aoife Brady

By Her Hand: Personal Thoughts and Reflections on an Exhibition, by Oliver Tostmann

Sister Eufrasia Burlamacchi (Lucca, 1478–1548), by Loretta Vandi

Giovanna Garzoni’s Portrait of Zaga Christ (Ṣägga Krǝstos), by Alexandra Letvin

Sister Eufrasia Burlamacchi (Lucca, 1478–1548), by Dr. Loretta Vandi

Artemisia Gentileschi: What Wasn’t in the London Exhibition and Why it Matters, by Jesse Locker

Suor Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596–1676), Convent Artist, by Angela Ghirardi

Elisabetta Sirani of Bologna (1638–1665), Guest post by Adelina Modesti

“I feel again the violence of a curious desire”: Rare client testimonies on Rosalba Carriera’s erotic art, Guest post by Angela Oberer

Lavinia Fontana: Italy’s First Female Professional Artist, Guest post by Elizabeth Lev

“La grandezza del universo” nell’arte di Giovanna Garzoni / “The grandeur of the universe” in the art of Giovanna Garzoni (Guest post/review by Sara Matthews-Grieco)

Plautilla Bricci (1616–1705): A Talented Woman Architect in Baroque Rome (Guest post by Consuelo Lollobrigida)

Do We Have Any Great Women Artists Yet? (Guest post by Sheila ffolliott)

The Politics of Exhibiting Female Old Masters (Guest post by Sheila Barker)

Sister Caterina Vigri (St. Catherine of Bologna) and “Drawing for Devotion” (Guest post by Kathleen G. Arthur)

Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596-1676), Convent Artist (Guest post by Angela Ghirardi)

Why Do Old Mistresses Matter Today? (Guest post by Merry Wiesner-Hanks)

New Adventures in Teaching Art Herstory (Guest post by Julia Dabbs)

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves (Guest post by Katherine A. McIver)

The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian, by Emma Steinkraus

A Tale of Two Women Painters (Guest post by Natasha Moura)

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective (Guest post by Judith W. Mann)

Outstanding! It’s always so beautiful to read you… I’m waiting for your new book about Artemisia Gentileschi, ordered since this spring.

Our happy thanks to Dr Mary D. Garrard for contributing this superb essay to Erika Gaffney’s Art HerStory e-newsletter. The historical content, the image selections, the overall treatment … a thrill to see & read. Artemisia is certainly having her moment!

And for a long time desired!

Continuing success to the Art HerStory virtual community,

Maureen E. Mulvihill, PhD.

Scholar & Rare Book Collector

Princeton Research Forum, Princeton, NJ.

Submitted July 1st, 2020.

_________________________

Thank you very much indeed to Dr Mary D Garrard for your lovely informative essay and paintings of Giovanna and Artemisia. I think when Artemisia first met the very young Giovanna and saw her ability she must have been quite shocked since Artimisia developed those skills when she was somewhat older. Later she must have seen it as quite a compliment when Giovanna painted a self portrait of Apollo in the style of Artemisia’s Lute player. Easy to see that Giovanna learned a lot from Artemisia even though each followed quite different paths with their art. Both women were magnificent artists and trailblazers for all the women artists to come through the centuries.